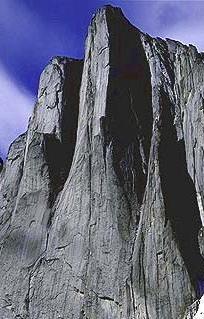

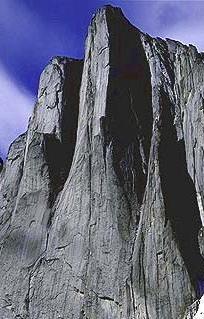

Route goes right up center of photo.

Copyright © 1988 by George I. Bell

|

|

The Lotus Flower Tower.

Route goes right up center of photo. Copyright © 1988 by George I. Bell |

All is silent aside from the monotonous dripping of water. The rain stopped two days ago but the rock here is still wet. Occasionally I hear signs of the struggle above me as Don curses at the slimy cracks, his hands stiff and knotted by cold.

Directly above me the snow wall overhangs, with a profile resembling that of a breaking wave. I feel like a surfer slicing down the face of a wave, the action frozen as the water curls overhead. Only this wave of ice would crush me into a wall of rock. The thin strip of sky above is my only exit, and I fix my attention on it and the thought of escape. Twenty pitches overhead, sunlight touches the summit rocks, but I shiver in the depths of this claustrophobic icebox.

My mind searches back for images of warmth and drought -- spring in Yosemite. Acres of sun-warmed vertical granite, sliced like hot loaves of bread by perfect crack systems. The exhilaration that comes with ten pitches of air below you, while the rock stretches endlessly above. But intertwined with these positive images are some that I would rather forget -- irate rangers presiding over crowded campgrounds,

"Rock!", the sudden cry brings back reality and immediate terror.

I am pinned in this position, unable to dodge or seek cover. The brick sized rock accelerates down the face and ricochets through the moat like a ball through a pinball machine. I quickly look down to avoid getting hit in the face and draw my body under my helmet like a turtle. The rock scores well as it slams into my right knee. I vent a stream of curses at Don, mostly because my illusion has been shattered. I could have spent these last two weeks in Yosemite, but instead I'm wedged in this miserable moat. I flex my knee experimentally, feeling no sharp pain. At least my leg is not broken.

This is our second attempt on the Lotus Flower Tower; one week ago we ascended half the route on dry rock only to be rained off the next day. Time and tempers now are running short; we both know that this will be our final attempt.

The first three pitches are wet, but at least we know the route. After the third pitch, the climbing is easier and the rock turns out to be drier. Smiles break out as the sun warms us and we swing leads up an easy chimney. We mark our progress up the clean granite of Huey Spire across the valley, while its shadow creeps across the brilliant green meadow below. How quickly the sun makes me forget the throbbing of my knee. The rock is solid and with each pitch the final headwall grows slightly larger. Now I have no need to escape into my warm Yosemite illusion, for reality is even better. Only the occasional ledge or deep crevice, brimming with moss, reminds us that we are not in Yosemite Valley.

|

|

A rainy day at Fairy Meadows

Copyright © 1988 by George I. Bell |

Wexler's pronouncement of these peaks as unclimbable caught the attention of the mountaineering community. Bill Buckingham, a young mountaineer with a voracious appetite for Teton and Bugaboo ascents, organized an expedition to the Logan Mountains in 1960. Over a period of a month, his team succeeded in climbing nearly every high point in The Cirque, by means of intricate and devious route finding which bypassed the major walls. Their greatest success was an ascent of the Proboscis, a curious bald fin of flawless granite which had stymied all previous attempts. Buckingham and his crew tackled the south ridge, which appears deceptively easy due to its low angle. The head on view was horrifying, but they persevered over level sections draped by the shrinking remains of cornices precariously clinging to the smooth granite snout, and steep vertical steps where aid was required. Not overly difficult by today's standards, this line still requires a solid repertoire of mountaineering skills.

Although the high points had been reached, the main walls of The Cirque remained as impenetrable as ever, awaiting a new breed of climber more accustomed to vertical granite. Again it was the Proboscis that captured the attention of several Yosemite pioneers. When viewed from the south, this peak appears remarkably similar to Half Dome. Indeed, early accounts of the Proboscis refer to it as "a mountain sheared in half", because it appears to have been bisected by a primeval knife. The polished white face formed by this bisection is 2000 feet high and an incredible likeness to Half Dome's sheared-off northwest face, complete with a zebra striping of black water streaks. It should come as no surprise that Royal Robbins was attracted to this face, as in the sixties he was the driving force behind every first ascent of Half Dome's northwest face. In 1963, Royal Robbins and Dick McCracken completed the first ascent of Half Dome's Direct Northwest Face. Two months later, joined by Valley locals Jim McCarthy and Layton Kor, they pulled off the first ascent of the southeast face of the Proboscis. This ascent was one of the first examples of Yosemite big wall techniques applied in a remote alpine location. The Proboscis has since faded into obscurity, and its southeast face awaits a second ascent.

The Lotus Flower Tower was the next peak to attract attention. This peak is not a significant high point, and is scarcely identifiable as a separate peak on a topo map. Characteristically, it had been named and climbed by Buckingham's expedition as they traversed along a connecting ridge. Nonetheless, like the Nose of El Capitan, the 2000 foot sweeping southeast buttress of the Lotus Flower Tower is one of the most striking sights in The Cirque. In 1968, three climbers honed by Yosemite walls pioneered a spectacular route directly up the prow of this buttress, since popularized in the book Fifty Classic Climbs of North America.

Big wall climbing in The Cirque became increasingly popular through the early seventies, and new route activity reached a peak in 1977. The summer of 1977 was comparatively wet, but as many new routes were established that summer as during all previous years. The 1968 route on the Lotus Flower Tower also received its first free ascent. Although climbers continued to visit The Cirque in ever increasing numbers after 1977, they seemed to lose interest in first ascents.

During the seventies two trends emerged which continue to this day. The first is the tremendous popularity of the 1968 route on the Lotus Flower Tower, and deservedly so for it is undoubtedly one of the best rock climbs in the world. Presumably the lack of readily available information on other climbs in the area has contributed to this trend. Many modern climbers in The Cirque (including myself) are unaware that most of the other towers in the vicinity even have names, much less routes on them. Few climbs aside from the Lotus have been repeated. The second trend is the large percentage of foreign climbers in the area. Even today about half the expeditions to the area originate outside of North America. In the last twenty years three quarters of the first ascents in The Cirque have been made by Europeans or Japanese. This is a remarkable statistic, and one may speculate that either The Cirque has escaped the notice of many American and Canadian climbers or it indicates more of a willingness among foreign climbers to climb wet rock during unsettled weather.

Recently, Don Mank and I spent two weeks in The Cirque of the Unclimbables. The standard approach is identical to that used by Wexler in 1955, involving a lengthy drive up the Alaska Highway and then a short (but expensive) hop via float plane (see logistics section). Glacier Lake, the landing point, is an easy day away from Fairy Meadow.

After we were rained off the Lotus Flower Tower, we climbed the southeast ridge of Crescent Peak during a day of unstable weather. This route is mostly exhilarating fourth class, and affords a spectacular view of the entire Cirque of the Unclimbables. In the final days of our stay, we concentrated our efforts once again on the Lotus.

|

|

The first pitch off the bivy ledge

Copyright © 1988 by George I. Bell |

Don unshoulders a small day pack, containing all our supplies. We lay down coils of rope to act as a pad, and pull a single sleeping bag over us as a cover. That morning we noticed that the lower section of the route acted as a gigantic drain pipe for the upper headwall, and lack of water was the farthest thing from our minds. Baking in the afternoon sun on the bivy ledge, my throat feels like sandpaper and I suddenly realize our miscalculation upon removing our single liter of water. From that moment on, the removal of "the bottle" becomes a significant event and we argue like two alcoholics sharing the last fifth of whiskey.

As we settle down for the night, a head pops over the ledge, and we are soon joined by two other climbers. The leader wrestles with a mammoth haul sack, and it is soon apparent that their bivouac philosophy is completely opposite of our own. Out come pads, sleeping bags, and a veritable ocean of water -- eight liters. Paul and Andy dine in comparative luxury as Don and I munch gorp between tablespoons of water.

|

|

Pitch 13

Copyright © 1988 by George I. Bell |

|

|

Pitch 15

© 1988 by George I. Bell |

It is late in the day when we finally reach the summit. The sky has cleared and the low angle sun highlights the top of every rock tower. Nearby, the Proboscis thrusts its fiery snout into the air. Rather than risk rappelling in the dark, we elect to bivy here. Paul and Andy, we found out later, ran out of daylight near the roof and were forced to descend back to the bivy ledge.

I munch on handfuls of snow, but it only chills me and does little to relieve my burning thirst. As we settle down to another cold and lumpy night, we notice a jet track passing directly overhead. What flight path would lead over this remote location? The track appears to twist and roll like a thread of smoke, illuminated by a distant light source. Quickly we realize that this is no jet track but an unusually vivid display of northern lights. The show continues for several hours, taking our minds off thirst, cold and speeding the countdown to sunrise.

|

|

The Proboscis in the morning from

the summit of the Lotus Flower Tower Copyright © 1988 by George I. Bell |

The next day it pours; we realize our luck to have threaded our ascent through one of the windows of sunshine. Leaving Paul and Andy with our extra food, and good luck for their next attempt, we head down to Glacier Lake. A tickling dryness in my throat is the only symptom of what is to become a serious throat infection which has me on antibiotics and a liquid diet for the next week.

Later that fall I resume my weekend pilgrimage to Yosemite Valley, joining ten thousand other worshipers. A day of strenuous but straightforward aid climbing on the Leaning Tower leaves the crowds behind and ends at a perfect bivy ledge. The weather, as usual, is flawless. The full moon rises to illuminate a scene I have been anticipating all week. As the air below us takes on an eerie glow, and the smell of wood smoke burns my nostrils, I have a sinking feeling the view will not be what I expected.

At night the normally placid Yosemite tourist feels a primal destructive urge and feeds any combustible item into the black hole of his regulation campfire grate. The result of several thousand smoldering pyres in such an enclosed space is normally a layer of ground smog, which no doubt contributes to the demise of the Valley trees. This night, an unusual inversion and complete lack of wind have slammed a lid on the valley, which is slowly filling with noxious smoke. By midnight we cannot even see the other side. A siren echoes off the walls, and I awaken with a start, thinking I am sleeping on a sidewalk in downtown LA.

|

|

Bustle Tower

© 1988 by George I. Bell |

If the Alaska Highway ran right past The Cirque of the Unclimbables it would undoubtedly be much more popular. Each morning a stream of climbers would issue from the campground up well trodden trails to the base of each wall. Experts would be competing for speed records on the Lotus Flower Tower and Proboscis. Fairy Meadow would be eroded by deep troughs from the constant foot traffic. In short, The Cirque would be even more like Yosemite. Thus, perhaps the most important aspects of the Cirque are the ways in which it differs from Yosemite: its isolated location, and the narrow windows of good weather. Any climber entering the Cirque today feels much the same sense of awe and remoteness that the first explorers to the region felt. Certainly this is a part of Yosemite that has been irretrievably lost.

Glacier lake drains into the Nahanni River, and this river was protected in 1972 by the formation of a National Park larger than Yosemite. Showing remarkable lack of foresight, the Canadian government did not include The Cirque of the Unclimbables in Nahanni National Park. This spectacular area thus lies unprotected from mining and other exploitations although it lies just a few miles outside a National Park. The Cirque is vulnerable to any number of abuses, and past accounts have mentioned the slaughter of marmots, and piles of trash accumulating in Fairy Meadow. Although in my trip to the area I found no evidence of such destruction, at present there is little to guarantee that they will not occur again. In reality it is only complicated and expensive access which protects The Cirque from the uncaring crowds that would destroy it. Let us hope that this scenic alpine area is preserved for generations of climbers to come.

Don Mank passed away at age 66 on October 1st, 2019. We had drifted apart in recent years, and I didn't realize his health had declined rapidly. It was sad to lose such a safe and motivated climbing partner.

Copyright © 1991 by George Bell of this page and all contents. All rights reserved.