|

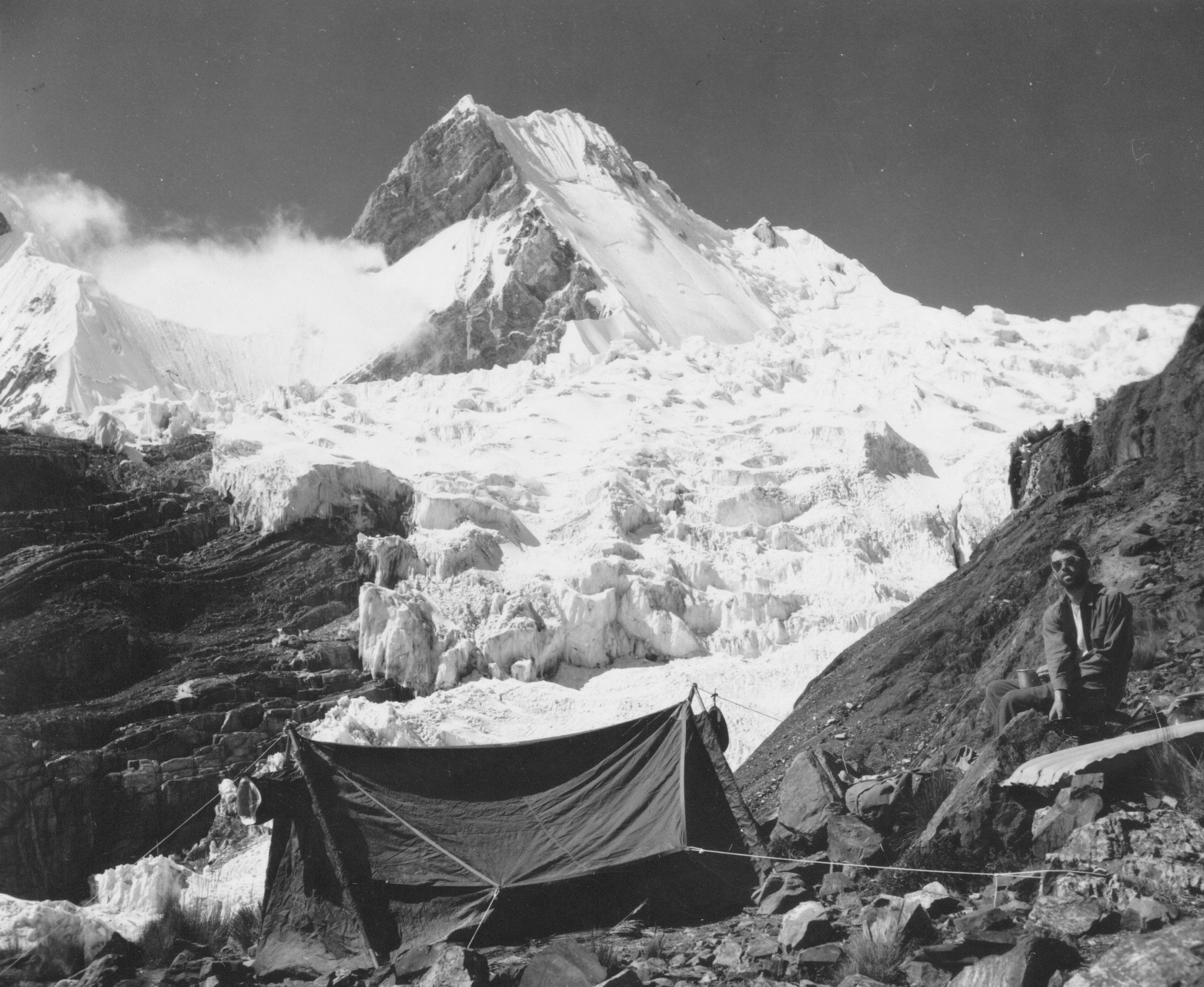

Dave Harrah takes a breather after setting up an interim camp. Across the glacier is the party's goal-the summit of Yerupaja. |

|

Dave Harrah takes a breather after setting up an interim camp. Across the glacier is the party's goal-the summit of Yerupaja. |

PHOTOGRAPHY BY THE AUTHOR

Saturday Evening Post, January 13th 1951

We knew it was a gamble—traveling 3700 miles to Peru to lay siege to a mountain never before climbed; a peak with a reputation so ominous that superstitious natives nicknamed it "The Butcher," and with defenses so formidable that many great Alpinists wrote it off as impossible. We couldn't even find it on most South American maps, this remote Andean tower, rising 21,759 feet above sea level, which bears the name of Yerupaja, meaning "World of Ice." That's a modest title for one of the most awesome mountains in the world—second in Peru only to 22,205-foot Huascaran; capstone of a mighty range separating the coastal plain from the jungles of the Amazon. But we were young, not easily awed, and willing to bet that this mountain could be conquered.

|

|

To assess the cost properly, picture Dave Harrah tumbling over the edge of a 4000-foot precipice, dangling for minutes at the end of a rope as taut as a bowstring, and then struggling half dazed up a wall of ice to safety on the summit ridge. That happened just a few minutes after he left the topmost pinnacle of Yerupaja. At the other end of his rope, 120 feet away, was Jim Maxwell, his companion on the last lap of the climb. If Jim had been yanked loose—and he nearly was—both men would have plummeted through space to certain death on the glaciers below. Yankee luck was with them, and they needed it, for The Butcher also had his eye on Jim. Minutes later, Jim broke through a thin strip of snow, with nothing but air beneath it. He jumped back just in time to save himself.

By now, the wind was rising and pitch-blackness was closing in as Dave and Jim struggled down the long rooftop of Yerupaja, finally huddling together, exhausted, in a tiny cave in the snow. The next morning, with feet frozen nearly solid, they stumbled down to warmth and shelter at High Camp, our topmost tent pitched on a narrow shelf of ice nearly four miles up in the sky. But we didn't know, until late the next day, that they were safe.

You might assume, after finishing this catalogue of horrors, that The Butcher had been paid in full. Dave and Jim know otherwise. Dark-haired Dave, a Stanford University senior, has lost all the toes on both his feet. Jim, a senior in geophysics at Harvard, spent two months in Lima and Boston hospitals recuperating from frostbite. Doctors had to cut away parts of almost every toe. It was a costly trip for Dave and Jim, but they figure it could have been much more expensive. After all, you can still go mountain climbing without toes.

|

We troops in the supply echelon didn't get off scot free. I contracted a fever, a temperature of 102 degrees, that forced me to turn back after starting with Dave for the top. Intestinal infections, fever or both sapped the resistance of the other three men—Charles Crush, high-school teacher from Salinas, California; W. V. Graham Matthews, an old Harvard classmate of mine and English teacher at the Fessenden School, West Newton, Massachusetts; and Austen Riggs, a graduate student in biology at Harvard. When you're toting forty to sixty pounds up sixty-degree ice slopes with your lungs crying out for more air, even a minor illness can wear you down. I lost twenty pounds during the thirty-odd days we spent on the flanks of Yerupaja.

Now that it's over, I don't feel cheated because illness ruled me out of the last climb to the summit. By staying below, I had a grandstand seat for a great mountain drama, and I have some memories that time never will erase. I can see them now, in retrospect—two tiny figures inching their way upward toward the clouds that capped the top of Yerupaja. Then the mist came down to hide them, just as it hid George Leigh-Mallory and Andrew Irvine on the uppermost slopes of Mt. Everest, highest mountain in the world. Mallory and Irvine never came back. Everest still is unconquered. As the clouds dropped lower, I couldn't help wondering if this was Everest all over again.

Memory carries me back to the following day, August first, with a shrill wind keening around Yerupaja and clouds draping its flanks like a shroud. I don't like to recall our feeling of grim despair, straining our eyes for a glimpse of Dave and Jim, waiting for the hours to pass, and finally realizing at dusk that something must have happened to them. It's the most helpless feeling in the world, sensing that somebody is in trouble and that you can't do anything about it. To climb at night on an almost-unknown mountain would have been sure suicide.

But this was a drama with a happy ending, and that's the part of it I like best to relive-the next day, August second, when we worked our way high up the glacier on the western face of Yerupaja, with clouds above, but sunlight below. We almost gave up hope as the day dragged on. Then, late in the afternoon, we suddenly heard Dave's hoarse "Help! Help! Help!" and realized that he was still alive, though in need of aid. That was a heart-stopping moment. For sheer satisfaction, it still ranks above the later moment when Dave and Jim, stumbling down through shattered blocks of ice to join us below High Camp, confirmed what we had hoped for. They had climbed Yerupaja.

You may wonder why we set such store by this mountain—why any mountaineer wants to climb a peak that no one else has ascended. The answer, I guess, is that a mountaineer is a gourmet. A virgin peak to him is like a new masterpiece of cooking to a man who fancies good food. Every climber with experience on big mountains—and there are a lot of such men—has a mental list of the untouched summits of this world. Very often, a good many Alpinists will be thinking of climbing the same peak. That happened to be the case with all six of us.

Just to show you how we got the idea-almost by osmosis, you might say-I will cite the example of Maxwell, Matthews and myself. We had been climbing together for three years as members of the Harvard Mountaineering Club. I graduated from Harvard in 1947 and went on to Cornell University to do research in physics, but I still kept up my mountaineering friendships. In the summer of 1948, the three of us made a trip to the Coast mountains of British Columbia-a wild, remote and thoroughly tempting chain of mountains. We spent our idle hours yarning, as mountaineers are apt to do, about the last great summits still to be climbed. A Harvard mountaineer, Bill Jenks, had worked for the Cerro de Pasco mines in Peru, and had carefully compiled a list of Peruvian peaks not yet conquered, among them Yerupaja. We discussed that mountain rather wistfully, and then let the subject drop. Peru seemed too far away.

|

The literature about Yerupaja was scanty, but I accumulated all there was. An Austrian expedition had first visited the Cordillera de Huayhuash, a mountain range which includes Yerupaja, among other icy giants, in 1936. Its leader, a Doctor Kinzl, made a detailed map of the area. Two other members of the expedition, Erwin Schneider and Arnold Awerzger, battled their way to the summits of Siul (20,800 feet) and Rassac (19,800 feet), but Yerupaja was too much for them. They made two bold attempts on that glittering mountain, reaching 20,000 feet on the southwestern ridge of Yerupaja, and then turned back defeated. Schneider, at least, was hopeful. He believed that a strong party probably could climb the peak by following its southwestern ridge, and by this route alone.

As for other climbers-Americans and Europeans who looked at Yerupaja from a distance, reconnoitered its foothills and launched abortive attempts on the summit itself between 1937 and 1948-their reports were uniformly intriguing. One veteran of the Himalayas called the mountain "the Peruvian Matterhorn," a reference to the Swiss peak which rebuffed all climbers until 1865, and has killed so many of them since. The late Frank S. Smythe, a member of the 1938 Mt. Everest expedition, is reported to have said: "First climb Kanchanjanga, then Yerupaja." That was chilling advice, since Kanchanjanga, one of the great Himalayan summits, is 28,146 feet high, the third highest mountain in the world, and probably more formidable than Everest. Nobody ever has climbed it, and there is some doubt that anybody ever will.

Maybe, in view of all this, I was foolish to keep harping on the subject of Yerupaja, but that's the way mountains get climbed. Somebody will say that a peak is impossible, and immediately a bunch of stubborn men will set out to prove the statement wrong. All through the fall of 1949, Austen and I amassed information. We located some exceptional aerial photos taken by a Swiss geologist, Arnold Heim, a copy of a report by Kinzl and Schneider, and every available statistic on the cost of a first-class climbing expedition.

By Christmas, 1949, we dreamers were about ready to take the plunge. We had pared our estimated costs to a rock-bottom minimum of $750 per man. We had saved up the money, and all we needed was two more climbers to bring our number to six. That's the safe minimum for a really big climb. Riggs, Matthews, Maxwell and I were committed to the trip. I then wrote Bob McCarter, an old Harvard m n, studying at Stanford Business School, and invited him to come along. That was how Harrah and Crush came to join us. McCarter, to our regret, was unable to take on any climbing during the summer of 1950. Since he couldn't come, he recommended Harrah, and Harrah in turn recommended Crush. They were strangers to us, but we knew them as first-class men. Harrah, who is only twenty-four, had been climbing in the Cascade Mountains since the age of thirteen, and thinking about such mountains as Yerupaja almost that long. Crush was a veteran of some spectacular rock climbs in the Sierra Nevada. A mature thirty-one, he was by far the oldest of our crew. I'm twenty-four, as is Maxwell. Matthews is twenty-eight, and Riggs twenty-five. All of us, by the way, are single men. Climbers who marry, I have found, develop a distaste for really interesting ascents. Either that, or their wives sensibly develop it for them.

During the winter of 1949 we couldn't run up and down any big mountains, so we kept ourselves in shape by a variety of home-grown expedients. I live 150 vertical feet below Rockefeller Hall, the physics building on the Cornell campus, so I ran up the hill to classes and down again each night. Harrah did his leg work on the steps in the Stanford Stadium. Riggs rode a bicycle two miles a day; Crush worked out with bar bells and weights; Maxwell had a part-time job as a tree surgeon, which is one efficient way of getting used to heights, and Matthews took long hikes. This wasn't very elaborate or formal training, but it seemed to do the trick, and it was in tune with the philosophy behind our expedition. We wanted to run it on the most informal basis possible.

We didn't even choose a leader, an omission which would make some of the great Everest climbers turn over in their graves. Each man took his own clothes, climbing boots, ice axes and crampons. Crampons are steel spikes, usually ten or a dozen of them, set in a metal framework. This framework can be fitted over the soles of climbing boots, strapped on tightly and used whenever ice or hard snow has to be ascended. Where boots would slip, the crampon spikes hold firm. As for food, usually the subject of much debate and calorie figuring on Alpine expeditions, Riggs and I worked it out over a few cups of coffee. Including a thousand feet of nylon rope, our food and equipment weighed 1500 pounds. It cost us $200 to ship the lot to Peru. We took only one formal step, and that was a wise one. We secured the sponsorship of the Institute of Geographical Exploration of Harvard University. That helped immensely in smoothing our way with the Peruvian authorities. We also had some scientific projects in mind as well as the climbing.

To make our climb, we had to hit Peru during the dry season, which extends from June to September. Riggs and I arrived by plane on June thirteenth-treated, en route, to a spectacular view of Yerupaja, towering above its surrounding peaks 100 miles north of Lima. It looked awfully cold and awfully far away. By the twenty-third of June all of us were assembled in Lima.

After a bitter struggle with Peruvian red tape, we got our food out of customs-the importation of foodstuffs being strictly forbidden, due to the shortage of dollars in the country. We added two caretakers for our Base Camp, Don Juan Ormea, an ornithologist at the Peruvian National University, and his son, Tomas, an expert at bagging birds. Jack Sack, a reporter for the Harvard Crimson, came along to help set up a two-way radio which was to keep us in touch with Lima-and which actually worked for ten seconds all the time we were on the mountain. Sack later went back to Lima, where he spent days vainly awaiting word of our progress and finally had to come in to base camp for news.

The Butcher was still a long way from us, but his defenses extended far down toward the coast. We penetrated the first of them, in the two-and-a-half-ton truck we had borrowed from a United States Army mission at Lima. We had to pass through a valley infested with a deadly, localized disease known as verruga peruana. Five thousand construction workers on the Central Railway of Peru perished of this disease-a particularly unpleasant one which causes the lymph glands to swell up, produces excruciating pain, and finally death within a few days. Natives are immune, but foreigners almost invariably succumb. The bacteria are carried by a tiny, almost invisible sand fly which is abroad only during a few hours after sunrise and before sunset.

Just as we were well into the area, our fan belt broke. We had no spare. We frantically thumbed down every passing vehicle, and finally succeeded in borrowing one that fitted, although badly. The day was wearing on, the time for the flies to come out was approaching, and we were still staggering along the valley floor. We would chug up a steep grade for half a mile, and then wait fifteen minutes for the boiling engine to cool. Often one of us would sit on the hood of the truck, reporting on the state of the engine.

It isn't boiling any more," an observer finally called back cheerily. He was right. It wasn't boiling any more, because it was out of water. We got just to the edge of the valley, having taken eight hours for the trip and having exposed ourselves to every fly in the countryside, when the motor finally quit. We spent the whole night of June twenty-seventh in a 14,000-foot pass, expecting any minute to feel the first symptoms of verruga peruana, and not until the evening of June twenty-eighth did we approach road's end at the town of Chiqui n, twenty miles west of Yerupaja. Luck was with us, all right. None of us contracted verruga peruana, though all of us save Austen and Graham had picked up some other kind of a bug and ran fevers between 100 and 103.

|

The mountains were impressive enough, but what really gave us pause was the cornices that adorned them, some of the most monstrous to be found in any mountain area. Great scrolls of snow and ice, built by winds blowing steadily from the Amazon Basin, they had formed on the lee, or western, sides of the ridges. Some of them projected horizontally more than 100 feet into the blue mountain air—millions of tons of snow, supported only on the inner side, ready to break loose without warning. Take a look at the cornice on any office building. Imagine that it's constructed of insubstantial snow instead of well-cemented stone, and you'll understand why we had some prayerful thoughts. To climb Yerupaja, we first would have to spend days beneath these horrors, and then we would have to walk on top of them. A man's weight can bring down a cornice in a flash. You have to guess where the rock of the ridge begins, and try to follow that invisible line. If you fail—well, that's why Dave Harrah nearly fell to his death, and why Jim Maxwell had to jump to save his own life. Cornices were to blame in both cases. So, before we started to climb, we looked hard at the cornices, and we looked at the ice avalanches thundering down over the precipices of Rondoy, and at night, when we could not see them, we could still hear them.

|

Dave and I pulled out at 8:30 on the morning of July tenth, carrying all that would be needed to establish our next highest camp-a two-man tent, two sleeping bags, air mattresses, a gasoline stove and food. It was the beginning of that long and tedious search for routes that always slows up an expedition. In the movies a group of mountain climbers may start right up a mountain without worrying about preliminaries. In real life you have to spend days working out your route, toting loads that almost break your back, and sitting out stormy weather in glum boredom far lower down the mountain than you'd like to be. It was that way on Rassac, a thoroughly nasty sort of ridge chopped up into minor peaks, gulleys and tilted cliffs.

It took us six hours to find our way through these, marking a route with piles of stones to indicate the way to those who would follow. We came out around the edge of the ridge and found a good site for our next camp at 16,100 feet elevation. Climbers get a special reward in the form of scenery nobody else ever sees from close up, and Glacier Camp was worth all the effort it took. We were actually high above the glacier, looking out to the formidable battlements of the mountain we intended to climb. Dave was to develop a theory that you should eat a limited diet at high altitudes-such dismal things as crackers and jam, hot tea and cereal. But, inspired by the view and optimistic, we dined that night on canned veal, baby beef liver, Finnish cheese and mincemeat. Theory or no, we had seen to it that there was plenty to eat.

|

We slept there the night of the twelfth, and the next day climbed out onto the shattered, broken floor of the glacier, first putting on crampons, tying ourselves together with 150 feet of nylon rope and unsheathing our ice axes. Our point of contact with the glacier was near the top of an icefall. A glacier, after all, is a river of ice moving slowly downhill, perhaps only a few feet a year. When a river drops down a steep incline, you have rapids or waterfalls. When a glacier does the same thing, you have an icefall. Great towers of ice hung over our heads as we climbed. Deep crevasses, yawning chasms in the snow so deep that we couldn't see to the bottom of them, made us move with caution. The Butcher was showing his teeth.

Above, we emerged on a relatively level snowfield leading up to the col, like a huge and snowy lap rug on the mountainside. Above us hung the cornices on the giant western face of Yerupaja. At one point a mammoth section of the face itself had given way. A million or more tons of ice had swept down across the floor of the snowfield. It had happened once, and it could happen again. Under a withering sun, we kept on slogging upward. Great blocks of ice stuck out of the snow-chunks that could have crushed a man as if he were a fly. These had slid down from above. The rising sun, melting the ice, might bring more of them on our heads, but there was no other way up. It was not until 2:30 P.M. that we finally reached the col at 18,800 feet. When you are carrying forty pounds on your back, after that sort of trip-with the constant prospect of ice tumbling down from above, and with your shoulders aching under the load-you want to sit down and take a long rest. Which we did.

The south side of the col was alarmingly steep and the snow was soft and treacherous. We found a better spot, considering our limited choice, some twenty feet below and to the north of a crest. Here was a bergschrund, a cleft in the ice which is always found at the upper end of a glacier. The snow below a bergschrund moves downhill, though slowly. The snow above, replenished by frequent storms, stays firmly in place, and the result is a crack. The upper lip of the bergschrund, a projecting piece of ice, had fallen in at one spot, filling the cleft and providing a site for a tent. At one side, however, a mass of ice towered out above us. Dave bet me that the bottom would drop out before the top fell in, but I wagered on the multi-ton sword of Damocles over my head. Both of them creaked all night as we tried to sleep in our tent, but luckily neither one of us won his wager.

|

Above us, the whole mountainside was a mass of crevasses, spidery lines in the snow. Overhanging and unstable cliffs of ice loomed above us, but none of them had fallen during Dave's stay at Col Camp, so we climbed with confidence. It was good footing, but as steep as a barn roof. We were traversing, moving diagonally across the slope, and we had to place our crampons with care, bending our ankles outward so that our bodies remained vertical while our feet assumed the same angle as the snow. That's a trick of climbers, and it certainly worked for us. The temptation, on a steep slope, is to lean inward, an almost sure way of guaranteeing a slip. We held our ice axes between us and the slope, using them for balance. In case of a possible slip, we could dig in the sharp point at the lower end of the ice ax and bury the wooden shaft in the snow. Or, if that didn't work and we began to slide, we could reverse the ax and dig in the curving, pointed head of the ax. An ice ax is built for such emergencies. The head of the ax, on one side, is shaped like an adz, for scooping footsteps in hard snow. The other side comes to a point, for chopping steps in ice.

This sort of climbing might frighten the wits out of an inexperienced man, but we were used to it from our past experiences in the West. By noon, threading our way upward, we reached a level space barely large enough for a tent. Below, the snow dropped away steeply; above, an overhang of ice bulged out about five feet. Dave, emulating a human fly, swarmed up alongside this overhang, drove a tubular ice piton-a round metal spike, hollow inside, which freezes solidly into the ice-attached the rope to it and slid down to our platform. Then we pitched the tent and went to bed-the only thing to do at this altitude. We were 20,600 feet up in the sky, and about 400 feet below the crest of the Yerupaja ridge, a long knife edge leading toward the summit.

Shortly after dawn, well chilled by a sleepless night, Dave and I started up toward the summit. Since we had not eaten for twenty-four hours, it took me only a few minutes to realize that I couldn't make it; that I would have to replenish my strength with food and drink below. At Col Camp I was glad to turn over my end of the rope to Jim Maxwell, who was feeling fine. I managed to get down to Glacier Camp, but for several days Dave and Jim were pinned down by high winds and snow. The Butcher was brewing more trouble. On July twenty-eighth, we could see them advancing over the west face from Col Camp toward High Camp, and then there was no sign of activity until July thirtieth. The winds blew up as they climbed above High Camp, and we saw them descend once more to their tiny tent. The mountain, it seemed, was playing cat and mouse with us. I was alone at Glacier Camp. Above me the wind was thundering continuously, and the clouds were tearing themselves to fragments on the great peaks. But at 10:00 A.M. on July thirty-first I caught sight of the climbers. Nearly a vertical mile above me, I saw two figures moving upward. The final bid for the summit was now under way.

The climbers continued upward. As they hacked their way up the last ice cliff before the crest of the ridge, the clouds swept down and swallowed them. Above 20,000 feet, the storm had spread its great gray wings. And then it was night and there was nothing to do but wait. Chuck, Austen, Graham and I were by now sharing two tents at Glacier Camp.

"Something is wrong," we decided late the next day, when we still saw no sign of anyone descending to High Camp. "Tomorrow morning we'll all go up the glacier and see if we can raise anyone by shouting. If not, two of us will go up to Col Camp and spend the night there. Next day the col party will go on to High Camp. They can display an orange flag if they need more help. The rest of us will watch from below."

The next morning we climbed slowly up the glacier. Clouds still scudded across the peak. We shouted. There was no answer except the muttering of the wind and the echoes from the ice walls. There were tracks of new avalanches across the route between Col and High camps. Could they have been trapped in a sudden fall of snow and ice? We went on up the glacier and shouted again. This time we could hear a muffled reply. At least we thought we could. We passed almost directly under High Camp and shouted once more. The wind died down for a minute, and this time we could hear clearly. It was Dave. In a hoarse voice he was calling for help. He repeated his call three times. That's the international distress signal, in use universally among experienced mountaineers.

"We're coming!" we shouted back. There was no time to lose. Chuck, we decided, would stay on the glacier to watch for anyone coming down from above. Austen Riggs would go up to Col Camp and keep hot tea brewing. Graham Matthews and I would stop at Col Camp for the night and go on to High Camp the following morning. We hurried up to the col, and were just finishing supper when suddenly we heard the cry for help again. Slowly and painfully, Dave and Jim were descending from above on frozen feet. They were shattered men.

"We've got to get down to Glacier Camp tonight," Dave was almost sobbing when we reached him. "We've got to get off the glacier tonight. If we ever take our boots off, we'll never get them back on. We've got to get down, so the doctor can amputate my feet." He was convinced that he was going to lose both feet.

Jim was worn out. He couldn't face the trip to Glacier Camp. So I descended with him to Col Camp, while Dave hobbled painfully on to Glacier Camp with Austen and Graham. That evening, for the first time since we reached the Cordillera, the sunset was a bloody red. In the darkness that followed, Jim told of the climb.

It was relatively easy, he said, until they reached the top of the summit ridge. The giant cornice, which draped itself out over the western face, had split at the crest of the ridge, opening a crack 30 to 100 feet deep. The climbers had no choice. They descended into its depths. Sometimes the crack was wide above them. At other times it narrowed and closed over them, and they advanced through a tunnel. Great masses of ice had fallen in from above, and these had to be climbed over. Once Jim dropped through the bottom of the crack up to his chest. He climbed out, after a desperate effort, and then looked down into the hole. Below him was only inky blackness.

Finally, this nightmare crack ended and they emerged on a ridge twenty-five feet wide, walking on top of the cornice, trying to stay on the line of the ridge. Through the mists there loomed up a giant pyramid, 300 feet high, plastered with thin ice and loose snow, an almost impossible obstacle. But there was a way out. Along the extreme left edge of the tower there was a small rock rib covered with snow, poised over the dizzy slopes of the western face. It wasn't a safe route, but when you're trying to bag such a summit you have to take chances. Very deliberately and very slowly, they made their way up this rib. Dave was ahead, whenever possible braced, with the rope around his hips, to hold Jim in case of a slip. In cold fact, if Jim had fallen, Dave would have been yanked from his insecure perches. Above the tower the ridge sharpened. Slopes of smooth ice and jagged rock fell off at sixty to seventy degrees from the horizontal. Tiny cornices protruded over the edge of these walls. By comparison with the pyramid it was a stroll to the summit. At five in the afternoon, they reached their objective. It had taken seven hours to go less than a quarter mile.

I have said we were an informal party. We deliberately neglected one of the formalities dear to the heart of mountain expeditions. It is customary to unfurl a flag, the national emblem of your particular country, when you reach a virgin summit. The Nazis were great hands for that, always taking pains to tote with them a swastika flag of prodigious size. We didn't even send along a flag the size of a pocket handkerchief with Dave and Jim. We didn't have one to send. We were climbing Yerupaja as sportsmen, not as representatives of the U.S.A., but the mountain staged its own display for us. Just as Dave and Jim reached the top the clouds parted, receded and dropped below the crest. They could see the whole Cordillera. They shook hands solemnly, took a few photographs and started back down the ridge. Jim Maxwell is an amateur cameraman, and a bug on high-altitude pictures. I don't blame him for that, although his zeal for photography nearly killed him.

A hundred feet down the ridge, Maxwell paused for a picture. Generally, in a delicate spot such as the ridge of Yerupaja, the climbers belay each other. In other words, at least one of them is braced to hold his companion in case of a slip. Both Dave and Jim were tired and in a hurry. Harrah didn't bother to jam his ice ax into the snow or to wind his climbing rope around it. That would have secured Jim against a slip and possibly made life pleasanter for Dave a moment later.

"I heard a cracking sound," Dave told me. "I saw the snow open between my feet and felt myself hurtling down in the middle of tumbling ice blocks. 'What a way to die,' I thought. I had time, though, for a few reflections on the concept of hubris, the ancient Greek concept of wanton disregard of natural order which plunges a man to doom. These reflections lasted only a second. Then I felt three awful squeezes around my middle, where I was tied to the rope, one squeeze after the other. I was a ball at the end of more than 120 feet of elastic nylon, bouncing up and down.

"My ribs felt like jackstraws. Jim shouted that he could not help me. I climbed ten feet straight up on the rope until I could reach a ledge, and then spent the best years of my youth clawing my way back up the ice slope. With one hand I dug my ice ax into the rubbery ice. With the other I hooked onto tiny projections with an ice hammer, which has a hook on one side. I don't know how long it took me to crawl over the edge again, but it felt like a year." What happened above as Harrah tumbled through the cornice?

"I saw the snow give way," Maxwell told me. "I grabbed up my ice ax, took a couple of steps over the top of the ridge, flopped down in the snow there, drove my ice ax into the snow, put one hand on the ax to brace myself, and then felt the first of three violent tugs. I couldn't have held on if there had been a fourth tug. I would have gone over the edge too. What saved us both, I guess, was the fact that the rope cut a deep gash in the snow on the ridge. That took some of the dead weight of Dave's body off me and absorbed the worst of his bounces."

|

In the morning when the sun rose, they made their way down to High Camp. They brewed hot lemonade on a gasoline stove, rolled up in their sleeping bags at eleven o'clock and rested for twenty-four hours. That next afternoon they saw us and we saw them. The climb was over, but we still had to get the cripples out to civilization. It was August fifth, three days later, before they both got down to Base Camp. We strapped Dave on a mule—he couldn't walk by then—and sent him out to Chiqui n. A taxi there drove him on to the Anglo-American Clinic at Lima. Jim's feet didn't trouble him quite so much. He rode out with the rest of us to Chiqui n on August tenth, waiting until we had dismantled all our camps and loaded the equipment on mules. We were all back in Lima by the thirteenth of August, but the doctors didn't amputate Dave's toes for about two weeks.

Dave remains undaunted. He knows that it will be many months or even years before he can balance and climb well without toes. But he said, "I'll get a special pair of boots made, so I can climb without my toes. I'll be back in Peru to try another mountain."

And he'll do it, I know. So, for that matter, will the rest of us. We have another unclimbed peak in mind, perhaps a tougher one even than Yerupaja.

I come from Winnetka, Illinois, which bears no resemblance to the mountain villages of the Alps or the Andes. People there and at Harvard and Cornell repeatedly have asked me why we want to climb such peaks as Yerupaja. The answer may be simple: To satisfy a natural human curiosity about the unknown. To pit yourself against the great forces of nature, and to win—that's an achievement. It's sport, it's fun, and it's something to remember with pride. The Indians, tilling their fields as we came out from Yerupaja, are less surprised about that sort of thing than most Americans. "Did you get to the top of El Carnicero (The Butcher)?" they wanted to know. "And is it really the highest mountain in the world?"

THE END