|

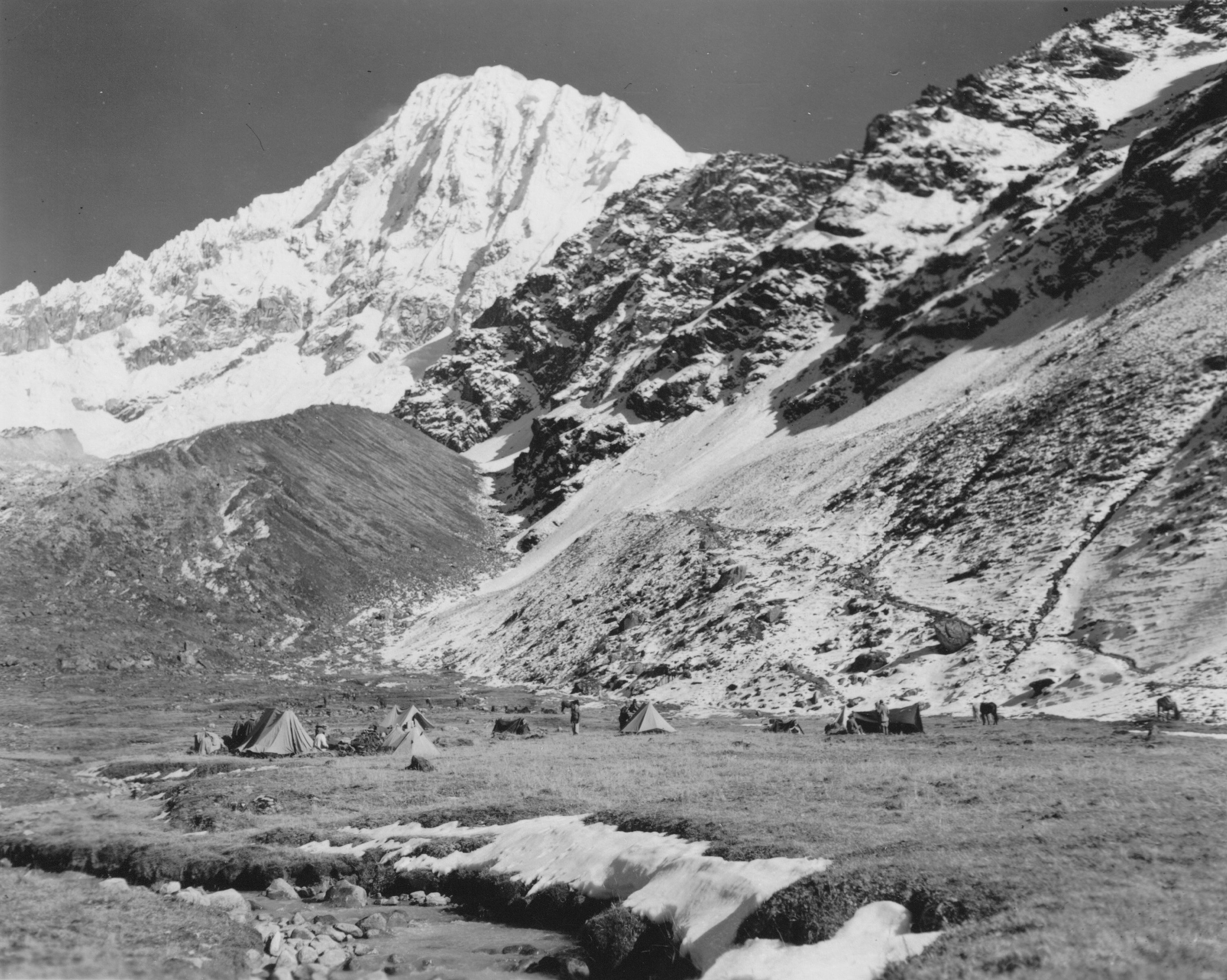

Members of the climbing expedition at Camp I on Peru's 20,000-foot Nevado Salcantay. Heavy snows flattened and flooded two of the tents. |

|

Members of the climbing expedition at Camp I on Peru's 20,000-foot Nevado Salcantay. Heavy snows flattened and flooded two of the tents. |

PHOTOGRAPHY BY THE AUTHOR

Saturday Evening Post, February 7th 1953

Not many people ever fall hopelessly in love with a mountain, which undoubtedly is a good thing for the human race. Such a romance is bound to be one-sided, apt to be disappointing, and certain to divert a man's energy from safer and more profitable pursuits. My considered advice is to resist the temptation, bearing in mind that the courtship can be fatal to the suitor. I suppose I should know this better than most Americans, having had some experience with mountains of dubious repute. Still, it was love at first sight when the drifting clouds drew back, two years ago, and I looked up at the sheer north face of Nevado Salcantay, 20,551 feet tall, one of the loftiest unclimbed summits in the Peruvian Andes. I knew this was one mountain I had to climb.

Translated into English, Salcantay means "the most savage mountain," a gross understatement when applied to a tower of granite rising 6550 feet above the sun-baked meadows at its base, armored in millions of tons of snow and ice, and alive with the roar of avalanches. Seldom before had I seen such a mass of towering precipices, hanging glaciers and fluted ice slopes, pierced here and there by a spiny ridge and loaded with the most monstrous aggregation of tortured cornices and shattered pinnacles to be found outside a nightmare. But the average man's nightmare mountain is apt to be the very one with which a climber falls in love, particularly when most people say that it can't, or won't, be scaled.

|

It took two years to prove that estimate correct. For days on end, the mountain veiled itself in storms and forced us back. An avalanche big enough to swallow up a regiment swept down a gully within fifty feet of our tents at high camp, showering us with pulverized ice. But late on the afternoon of August 5, 1952, kicking steps up an almost vertical slope of frozen snow, I came out on a knife edge so narrow it had to be straddled. A numbing wind tore the clouds to shreds, and opened a vista toward the brown valleys below. With one climbing boot hanging down over the headwaters of the Amazon, and the other dangling over the Peruvian plateau, I was sitting on top of Nevado Salcantay. One of the last and most remote mountains of the Western Hemisphere had been climbed.

Six of us reached the summit of Salcantay that afternoon—four Americans and two French climbers, comprising the first Franco-American expedition in mountaineering history. It was one of the first expeditions of such difficulty to include a woman. To me, the finest moment of the whole climb took place when Claude Kogan inched her way out on the summit ridge—Claude, a tiny Frenchwoman only five feet tall, weighing less than 100 pounds, who turned out to be one of the bravest and most effective members of our entire party. I suspect that Salcantay represented a debt of honor to her. In 1951, after climbing another huge Peruvian mountain, her husband died of a gastric hemorrhage. In her early thirties, when most women might prefer to lead a quiet life, she carried on for him on Salcantay.

|

The ascent of Salcantay was a vindication in more ways than one. Merely reaching the foot of the mountain took us seventeen days, for snow blocked the high passes, and storms made a mockery of the "dry" season which usually desiccates this part of Peru between July and September. Wind, clouds and storm chased us off the north face three separate times. It seemed that we never would reach the summit ridge. Until we did, we could never be sure that we were first up the mountain. Two Swiss, residents in Peru, went in to Salcantay just ahead of us, and came out proudly claiming a first ascent. They actually climbed to the ridge of Salcantay and flew the Peruvian flag from that vantage point. Darkness and flagging energy turned them back less than a mile from the true summit, a cone of snow on the far side of a deep gap, scarcely fifty feet higher in altitude than the spot they reached on the ridge. What they accomplished was stupendous for a two-man party, but it wasn't a normal first ascent.

In retrospect, it amuses me to realize how close we came to omitting the French from our expedition, for reasons which seemed valid enough at the time. The big question was: Could we get along with these strangers, jammed night after night into tiny tents high on a mountain? Many a climber, galled by his tent mates, has seriously contemplated murder in the still hours of an Alpine night. We wondered whether they might be reckless, a trait that can send a whole climbing party tumbling to its death. I had some personal misgivings about Claude Kogan's ability to withstand the strain of the climb, even though she had a magnificent mountaineering record. Salcantay is no "easy day for a lady," the term once applied to the customary route up the Swiss side of the Matterhorn.

I am happy to acknowledge that I was wrong on both counts. When I saw Claude, crouched on a slope as steep as a mansard roof, chopping steps by the hundreds while merrily trolling a chanson, it was evident that she had both emotional and physical stability to spare. In 1951 she established a world's altitude record for women by climbing Quitaraju, a Peruvian peak 20,130 feet high, with Mme. Nicole Leininger. Bernard Pierre, thirty-two, who shared a climbing rope with Claude on Salcantay, proved also to be one of our most reliable climbers. A third Frenchman, Dr. Jean Guillemin, thirty-seven, back-stopped the expedition from base camp, and guided the four Peruvian porters who carried supplies up the north face to a point below high camp. The only difficulty with the French was a linguistic one. Among us all, we spoke four languages. I knew a little Spanish, and two other Americans in our party spoke French. Claude spoke Spanish and French only; Pierre was fluent in English, and Guillemin spoke English a little. The porters spoke only Quechua, an Indian language, which none of us knew.

The Americans in the party were all old climbing friends. Graham Matthews, a lanky, bespectacled thirty-one, was with me on Yerupaja. When not on a mountain, he teaches geography and history in West Newton, Massachusetts. Fred Ayres, still a fine climber at the age of forty-five, left a job as an industrial chemist in the East to teach at Reed College, in Oregon, close by the great snow peaks of the Pacific Northwest. David Michael, twenty-four, is an art student in New York, and a climber with experience in the Coast Range and Alaska. Two other members of the party had to leave us before we reached the summit. Austen Riggs, thirty-one, a research biologist, flew me down—a 3700-mile trip from New York. He had to go home some days in advance of our actual climb. John Oberlin, thirty-eight, stayed with us until we were well established at high camp. Then his vacation time ran out and he returned to a law practice in Cleveland.

|

Running in crampons is a delicate business at best. Unless you watch your feet, it is easy to trip-which, in our case, would have involved a cartwheel fall several hundred feet down the mountain. Shortness of breath slowed us down. It took several minutes for each crossing—and no chance to steal a look at the 200-foot ice wall that crowned the top of the gully, occasionally letting loose a lethal shower of ice chunks. We were lucky not to be caught in an avalanche, a fact borne in on us July twenty-ninth, when Salcantay produced an unmistakable warning of its power. To the west of our three tents at high camp, which were perched on a ridge of snow, another gully split the side of the mountain. We had just settled down at sunset when, from above, we heard a sharp, cracking sound. Then came a heavy, grating noise, followed by the thud of dozens of blocks of ice, any one of them big enough to sweep away a whole climbing party. Pulverized ice showered the tents. Stray chunks boomed within twenty-five feet of high camp.

Miscalculations can wreck the best organized of climbs, which may explain why we dealt with Salcantay so tenderly. Our reconnaissance started in the summer of 1950. We had just come down off Yerupaja after paying a heavy toll to that magnificent peak. Dave Harrah and Jim Maxwell, the only men to reach the top, froze their toes and had to undergo amputations. Obviously, they could not come with us to look at Salcantay. I saw my first pictures of the mountain in a book about the Andes published in Switzerland. A little later I read an account by Hiram Bingham, the explorer from Yale University, who made the first practical estimate of its difficulties. Around 1915 after discovering the ruins of the Inca fortress of Machupicchu, Bingham walked in to the base of Salcantay. It is, he said, a magnificent peak "which someday will prove a challenge to mountaineers." It was more than a challenge to me, that summer of 1950. It was a hopeless passion. We walked almost completely around Salcantay, photographing its sheer faces, its icy ridges twisting skyward. One by one, we noted down these ridges as "too dangerous to justify an attempt," or, more simply, as "impossible." One night, about two A.M., Graham woke me and pointed upward. We were sleeping in the open, without a tent. Through a rift in the clouds, by the dim light of a waning moon, we saw the upper slopes of an ice wall and the summit ridge thousands of feet above us. We agreed that this was it: Either climb Salcantay by the north face or not at all.

|

We planned the expedition with the utmost care. It does you no good to reach for an essential piece of equipment, halfway up a mountain, and then to discover that you've left it back in New York. John Oberlin collected some 357 different items, including such essentials as tents, ropes and other climbing supplies. He also made sure of our supply of waxed thread, potholders, shoe grease, gloves for cooking over an open fire, safety pins, mosquito dope, marking crayons for our maps, photo bags for changing camera films, and even clown white, a grease applied to the lips to reflect the sun and forestall blister. I made up a food list to cover 300 man-days of climbing. Expeditions to Mt. Everest, highest in the world, have written learned tomes on the subject of selecting food fit for high altitudes, the stomach being unpredictable above 15,000 feet. We dined like gourmets on such things as p t de foie gras, furnished by the French, and chile con carne.

|

On June twenty-ninth we motored from Cuzco to the trail leading in to Salcantay. Ahead of us were two 15,000-foot passes. That is no trivial height, when you consider that Mt. Whitney, California, the tallest peak in the continental United States, has an altitude of about 14,500 feet. The trip in, which should have taken two days, took more than two weeks. Fog and snow engulfed the mountains. The closest and easiest pass was hopelessly blocked until the snow melted and we crossed on July ninth. While we were waiting, the worst blow of all fell on us. A bearded mountaineer, his lips cracked and blistered by the sun, came hobbling into the little Indian village where we had bivouacked. His name was Felix Marx. "Believe me, gentlemen," he told us, "I have climbed Salcantay." With Marcus Broenniman, an engineer, Marx scaled the east ridge—no mean feat, as we discovered from a subsequent look at the mountain.

We took Marx literally, which left us with a grave decision to make: Should we climb Salcantay regardless, even if it proved to be a second ascent? The decision—a tough one for any mountaineer—was that we should go ahead. I felt this strongly. The others concurred. After all, we were footing the bill for twenty-nine pack horses, ten mules, four porters and four drivers, not to overlook the costs of our trip to Peru. There was always the possibility that Marx might be wrong. Before we left our first bivouac, John Oberlin went out to Cuzco and returned with a newspaper clipping that seemed to prove it a gamble worth taking. The clipping was an account of the Marx-Broenniman ascent. An accompanying photo from the summit ridge plainly showed in the distance a cone of snow that was higher.

|

Above Camp I, our troubles began. A band of cliffs crossed the route, from which great masses of ice toppled. To make things more awkward, it was boiling hot. Salcantay is only thirteen degrees, a few hundred miles, south of the equator. Sunlight reflecting from the snowfields can shoot the temperature up to 100 above during the day and yet it may drop to a chilly fifteen above at night. Baked by day and frozen by night, we hacked away at the mountain, and finally found a site for high camp on a tiny snow-and-ice promontory. Our Peruvian porters, still cherishing a healthy respect for the spirit of the mountain, refused to be cajoled higher than a point about half that distance. There they dumped their loads in a shallow crevasse—a split in the ice—and climbed down the ice slopes, using a fixed rope as a hand line in the steepest places—carefully belayed by one or more of the climbing party.

Above us, the next morning, we could see a storm closing in. Claude, Bernard, Fred and I had spent the night at high camp. We worked our way up past two huge crevasses, at which point Claude took over the lead and proved her merit beyond cavil. She chopped away at the ice slope with a vengeance, showering ice and snow on poor Bernard. He was crouched far below her, at the other end of the rope, holding her secure in case of a slip. When I relieved Claude, the clouds closed in and I was alone in an eerie setting, solitary on a smooth ice slope, out of sight of people, rock and tents, with nothing but clouds and smooth ice for companions. An advance was impossible, and by midday of the twenty-fourth all of us retreated to base camp as a blizzard wind moaned high above. It was July twenty-eighth before we regained high camp, exasperated and this time half frozen. We just managed to pass a third crevasse above high camp when the clouds swept in again. Above us, we could just make out a precariously balanced cornice and an ice tower over it. We began to feel like Yo-yos, an impression heightened on the thirtieth, when David and Fred worked their way into the very top of the ice gully, only to be turned back by a new storm.

That night the avalanche fell, providing a sufficient incentive to send us all down in the fog and snow to base camp again. It was August second before Fred and I climbed back up. This time, as before, we had to clean out the old steps we had chopped, and sometimes chop new ones where avalanches had filled them in. On August third we passed the three guardian crevasses and climbed to a point where the summit ridge was visible. The ice wall sloped sickeningly up to meet it. There were still hundreds of steps to be cut, but the end was in sight. That afternoon Claude, Bernard, Graham and David joined us at high camp. We drank our toast to victory in tea, and dined on p t aux truffes.

The mountain, however, had different ideas. Storm clouds swirled around the ridge and warned us against climbing any farther the next day. By August fifth we were thoroughly disgusted and determined to finish the climb, even though the sky still was ominous. We cut steps on a slope so steep that I had to clear a niche for my knee as well as a place for my feet. Fred, at the other end of my rope, enlarged each step with his ice ax, an instrument designed for just such occasions. The ice ax has a point at one end, a wooden handle and a curved head shaped like an adz on one side and like a pick on the other. The pick is used to chop out steps in ice; the adz, to clear and enlarge them.

The clouds closed in as we inched our way upward, but by two P.M. the worst was over. We emerged on the ridge. Ahead of us we could see the stump of a wooden flagpole the Swiss had planted there—and knew that our days of struggle and defeat, of painful inching into the mist and fog, were more than worth the effort. The true summit was still quite distant, poking its head into the clouds. The Swiss had told us that they went no farther than the flagpole. There was no doubt we had a first ascent coming up.

At first the ridge was flat and level, but then it dropped precipitously into a foggy gap. We drove a stout three-foot stake into the snow, tied the rope to the stake and descended to the gap. It was a scant 200-foot climb from the gap to the summit. Fred led the way. He was first on top. I followed him. A bitter wind keened around the knife edge. The clouds broke just enough to show us a few brown hills below. I was gasping for breath, trying to inhale enough air to fill my lungs. It was difficult to be very triumphant, and all too easy to be tired. Because the rooftop of Salcantay was too tiny to hold us all, Fred and I descended to the gap. Graham and David, then Claude and Bernard, passed us, on the way up to share the heady feeling of a first ascent.

The conquerors of an untrodden. mountain deserve, at the very least, the amenities of a hot bath, dinner at a table and a soft bed for sweet dreams. We slept that night in a two-man tent at the base of the Salcantay pinnacle, six of us wedged into that cramped space. To say we slept was an exaggeration. We dozed, tossing and turning, waking dozens of times during the twelve hours of darkness. Not until four hours after dawn were we able to face the self-evident fact that what goes up must come down. Graham and David went ahead, putting in fixed ropes for hand lines. Most of them we left on the mountain. At the high camp, everybody was there to greet us, including Abel Pacheco, the owner of our pack horses and mules, and Se ora Mayalay Fleury, a Peruvian friend of the French climbers. Even the porters were on hand, grinning and chattering, apparently convinced that the spirit of Salcantay could be successfully challenged.

The Case of the Unsuccessful Swiss was finally solved to everyone's satisfaction when we came out to the highway and back into Cuzco. Marx and Broenniman, who said that they had "climbed" Salcantay, admitted that their use of the term was a trifle loose. Most mountaineers don't claim to have climbed a peak unless they reach the summit. Marx and Broenniman were satisfied to reach the ridge. Broenniman himself admitted to us that from the ridge he had seen the final cone at a distance. "We restrained our desire to attempt this needle," he said in a newspaper interview, "realizing that it would first be necessary to es tablish a camp on the summit ridge." In a manner of speaking, considering the effort involved, I could understand why they stretched the facts just a little. Not only did they have a gruelling climb but on the way down a fixed rope gave way, and Broenniman fell hundreds of feet down the mountain. It was aheer good luck that fetched him up close to the tracks that led to their high camp. Marx was marooned for the night on a rock promontory. Broenniman's feet were so badly frostbitten that he was unable to walk without pain for months.

To climb such a mountain, however much you fall short of the goal, is an adventure of the spirit, a test of the soul and a challenge to the human will. From a distance, almost any great peak seems impossible, yet few of them actually are. But even after a climb such as the one we made on Salcantay, it is possible to wonder if it really happened. On the way out from Cuzco to the Peruvian coast in a Faucett Air Lines DC-4, the pilot obligingly flew far off his route and circled around Salcantay. As he put the plane into a steep bank, dipping his wings over the cliffs and ice pinnacles of Salcantay, I could make out below the faint and melting path of our climbing track. In a few weeks all the evidences of our visit would be obliterated, and the mountain once more would be a lonely fortress standing guard over the high divide between the Peruvian plain and the jungles of the upper Amazon.

My finest memory was of the last day at base camp, before we left the mountain to itself. Most of the time, Salcantay was hidden by clouds. Usually it could be seen fleetingly at dawn. That final day I rose very early. In the deep valleys and over the silent jungles there was a brooding mantle of darkness. But far above, flaming in the first rays of the sun, I could see the summit ridge of Salcantay, master of itself no longer. Now the mountain belonged to six of us.

THE END

View of the summit of Salcantay from the Southwest.