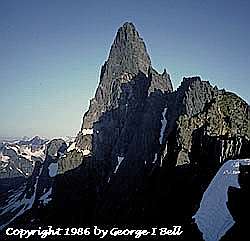

The NE Buttress of Mt. Slesse (morning) |

Fifty

|

The NE Buttress of Mt. Slesse (evening) [only upper third visible!] |

The NE Buttress of Mt. Slesse (morning) |

Fifty

|

The NE Buttress of Mt. Slesse (evening) [only upper third visible!] |

Once again the hood of my Subaru shot into the air. Momentarily, the entire contents of the car were in free fall. Quickly, though, the iron hand of gravity took control, and the car slammed down on the suspension, its descent finally halted by a sharp crack underneath.

"Shit!" I erupted - the automatic response of any car owner.

Moving barely faster then we could walk, we were bouncing up what appeared to be a dry stream bed, filled with nasty rounded boulders. Squeezing us from either side were large clots of Pacific Northwest vegetation, drawn by the magnet of increased sunlight. A suitcase-sized boulder appeared, and I spun the wheel crazily to the right. A wooden claw reached out and swatted the windshield, then squeaked and stuttered past the side windows.

Oblivious, Don Mank shuffled through the collection of xerox sheets that constituted our guidebook. "It's just like I told you," he said, looking at Fred Beckey's book. "Follow the road two miles to a creek crossing, then go four more miles to the end."

Progress ground to a halt. The din quieted to the gasping of the tiny, overworked engine. The path ahead was flooded; only the tops of those bone-jarring blocks were visible. I grabbed a loose water bottle that had rolled under my feet and hurled it into the back.

"Either Beckey's nuts or we made a wrong turn back there. We've gone hardly a mile, and this is a stream bed, not a road!"

The car straddled a narrow opening, the first place I had seen where we might turn around. I jumped out to check under the car for leakage of vital fluids. Don insisted that this had to be the route, and eventually I agreed that we should scout ahead by foot for awhile.

Compared with my battle in the car, walking up the stream bed was relaxing. But this was merely because the vegetable army had not quite closed over us. Staring into the depths of the forest, I saw a line of huge, thorny devil's clubs hiding warily behind a snare of willow shoots and moss-covered logs. If we did not find the right road, we might never even get to the base of our climb, the northeast buttress of Slesse Mountain.

|

| The infamous Honda |

Neither of us would have been there had it not been for that book. In just ten years, it has had a considerable effect on many climbing areas. How many budding climbers had received this book as a gift from well- meaning friends? How many times had these climbers later read another exciting account, dreamed, and eventually planned a climbing trip? When they finally visited the locations they had read about, they of course began with those dreamed-of routes.

This became a problem. The Fifty Classics became popular. They became crowded. People have become used to this in Yosemite and the Tetons, but now, even on a remote wilderness climb like Slesse, we had company.

Don and I were in the middle of a climbing tour of the Cascades. Knowing little about the area, we had relied on friends, guidebooks, and yes, we had to admit, Fifty Classic Climbs. During the previous two weeks, storms had forced us to the drier east side of the range. Finally, a period a clear skies had set in, and we had raced back to the coast to nail Slesse.

As we walked past the Honda, though, the small strip of sky visible to us was filled with a depressing overcast. The road began to rise slightly, and then ended dramatically at a snarling, fifty-foot-wide river. A mere "creek" in this region, it had recently removed all traces of the bridge. In such a rainforest environment, unmaintained logging roads had a short lifespan. Here, though, was an excellent campsite, a tent-sized spot of the old road that had withstood the combined efforts of floods and alder saplings.

Don was sure my Subaru could make it to this spot. "If that wreck can make it, so can your fancy four-wheel drive."

On the way back I took another look at the battered Honda. The front

bumper was deeply notched and the hood was dished-in, evidence it had met

a tree or post. One of the fenders could have been ripped off by hand.

Clinging to the front bumper were the tattered remains of a homemade

bumper sticker:

|

That did it. I wasn't about to begin competing with this driver, some kind of cruel lunatic. It was sheer nonsense for the mere quarter mile we would gain. We would have to settle for a lumpy site in the middle of the road.

In the morning we awoke in a dense fog, which appeared to seep from the trees themselves. Don soon uncovered a friendly reminder of the forest life around us--an enormous slug that had crawled into one of the cooking pots. We sat glumly munching granola while peering into the vigorous growth that surrounded us. These plants would surely die without almost constant watering; the only question seemed to be when the deluge would begin.

|

|

The approach "road"

Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

It seemed impossible, but it didn't dawn on us that we were still on the road that Fred Beckey had driven along on the first ascent twenty-three years ago. A mile later we realized what had happened. At this point the old road had passed very near the creek, and in a huge flood years back, the water had overflowed into it, removing twenty feet of soil and transforming it into what was now just another branch of the main channel.

Here we met the dejected owners of the Honda, who told us they had never even seen the mountain. Continuing up the roadbed, in several hours we stood at the base of the northeast buttress of Slesse, or rather, argued about where the base was. The fog was lifting slowly, and we tried to piece together the various parts of the mountain that appeared through holes. We waited.

Don is an electrician by trade, and a climber by obsession. He works just enough of the winter to support his lengthy summer climbing tours around the U.S., which last four to eight months. This had been his pattern for at least the last ten years. His co-workers thought him crazy; I thought he was the most intense climber I had ever met. Every day we would be up at first light, and no "rest days" were allowed. Like myself, Don had entered the sport through backpacking, and it was still backcountry climbing that he loved most. He disliked topos and preferred to leave even verbal descriptions at the base of routes. The sheer volume of routes he had done was amazing. From talking with him I estimated that in the Sierra alone he had done over a hundred technical backcountry routes. It was tempting to think of him as the modern-day Fred Beckey, but unlike Fred, Don seemed content to repeat the old classics. Even when he did venture on new ground, he had little interest in reporting his ascents. For Don, climbing was its own reward, and he expected nothing more from it.

We eventually realized that the weather would have to improve greatly for us to climb Slesse. We would have to climb something easier. "How about Rainier?" I suggested. "Surely we can find that in the fog." But Don would have nothing to do with what he considered a snow slog from any direction. We traipsed back to the car that day to consult our resources.

Like most younger climbers, we had lots of time but little money. All restaurants, including the local fast grease outlets, we considered too expensive. For long drives we had, in bulk storage, huge tubs of peanut butter, jam, and several cases of Top Ramen instant noodles. Even climbing guidebooks were thought of as an unnecessary expense. At the beginning of our trip, we had spent hours in the local REI poring over guidebooks. Don, laughing at my attempts to scribble details on sheets of paper, approached a secretary at the customer service department, and I watched in disbelief as he convinced her to xerox the 50 pages we had marked. This left us with a free, but rather disconnected, guidebook.

Some days later the weather had not changed, and we were rapidly exhausting our knowledge of routes that could be done under such conditions. Finally, Don issued an ultimatum: "Tomorrow. Forbidden Peak, alpine style."

Forbidden Peak? I had heard of that. It was one of the easiest of the Fifty Classics. But alpine style?

Don explained: "Minimum equipment, minimum information."

Minimum information. That would certainly be the case. I did seem to remember that the climb was in Washington, but without a copy of Classics, just finding the climb would be a considerable challenge.

To our amazement, the peak was shown on our highway map, and only one road went anywhere near it. Driving up this road, we easily spotted the start of one of the state's most crowded climbs--a small knot of climbers' cars. We looked inside them for the obvious signs: piles of faded slings, ancient ice axes, or the dead giveaway, a 'biner on the rearview mirror.

Despite overnight drizzle, we got an early start. Loading our packs with a bare minimum of gear, we followed a muddy path that quickly rose through the fog to timberline. Visibility was limited to a few hundred yards. We were nearing the crux of our ascent: finding the mountain.

"You mean you didn't even bring the map!" I said, referring to our state highway map. "How are we supposed to find this crazy peak?"

"No problem," explained Don, "we'll follow the most obvious path. Hundreds of people must have climbed it last weekend."

Before long we were totally lost. Trails led all over the place. We sat down, hoping the fog would lift.

Hours went by, and although our lunch disappeared, the fog did not. Our only hope lay in finding some other climbers. Evidently, this route did not get the traffic we had expected. I spotted what looked like a guided group, starting self-arrest practice at the base of a snowfield, and approached the leader.

"Say, you wouldn't happen to know where Forbidden Peak is?"

He pointed to the other side of the basin we were in.

"So, to do the west ridge, we would go to the right of that buttress that goes up into the fog?"

"Yep, but I wouldn't try it," he said. "The couloir's blocked by an impassable 'schrund."

I could not help noticing the mood of their entire group. The students looked completely bored by their surroundings and took very little interest in us. And these people were paying money for this? But there was no time to waste; we would have to move quickly to finish the climb. The guide had not seen the barrier bergschrund personally, and it began to sound more like a rumor. As we moved off, he became quite upset that we were ignoring his admonition, and called out that it was past noon and that we would never make it back before dark. We thanked him for his advice but did not slow down; this infuriated him even more. Puzzled by his behavior, we soon pieced together his view of the interaction.

Here he was giving a lecture on safety, and up march two climbers, violating every edict he had just taught. We could readily imagine the tongue lashing we were given: "Those two guys have made every mistake imaginable! They are getting a late start; they have no map, compass, watch, or route description, and they are continuing in bad weather when they have been told it is impossible! I think we may soon be involved in a rescue here."

Despite the guide's warning, the rest of the climb went easily, once we had located it. A lucky break in the clouds revealed the couloir leading to the ridge, and I was surprised to see we would have to traverse a glacier to reach it. I had not expected one on the south side of the peak and so had not brought my sunglasses. A line of footsteps appeared, and I led across the glacier squinting at them. They led, sure enough, right up to an impassable bergschrund. I had a headache by now and stepped left onto some rocks to reduce the glare. After Don led up through the rock beside the couloir, we were able to unrope and quickly move up the rest of the route.

On the summit we relaxed as the first rays of sunlight broke through the fog. As is often the case after doing one of the Fifty Classics, I began to reflect on the quality of the climb. Was this really one of the finest climbs on the continent? This type of question often sparks violent controversy, but Don was uninterested. All of the Fifty were excellent climbs, he said, and, for climbers such as ourselves who knew little about an area, they were always a good place to start. After climbing extensively in an area, each climber would develop his own list of favorites, and Fifty Classics was just one example of one such list.

The problem is that many people do not regard the Fifty Classics this way. For many climbers the Classics become the only climbs worth doing. We called these people the crowded-climb-baggers--narrow minded individuals who ignore any peak not in their bible and roam the country checking off their ascents one by one.

But something was bothering me. We had practically become crowded-climb- baggers ourselves. After all, had we not gone out of our way just to climb one of the easiest of the Classics?

"How many of the Fifty have you done now?" I asked.

Don scratched his beard with a heavily calloused hand hardened by months of rock climbing. It was easy to see why he never taped up.

He finally answered. "Twenty-eight."

I was astonished, not only by the number, but also by the fact that he was obviously keeping careful count. A horrible thought began to enter my mind. Wasn't it Don who had suggested this climb in the first place?

"Last winter I finally got hold of that book and counted," he added.

So that was the reason for the exact figure. I could not really see Don as a crowded-climbs-bagger anyway; the large sum was just a reflection of the vast amount of climbing he had done. But you can never be too careful these days. I could not resist a further jibe at his gross total.

"Pretty soon you'll have to move to Alaska and do some real climbing."

Don recoiled in horror at this thought. "Nah! The weather sucks up there. I'd rather spend a month in the Sierra than a month in a tent."

|

|

Mt. Slesse (NE Buttress is the left skyline) |

I hoped that these newcomers to the sport would realize that the essence of climbing is to be continually testing your limits, not listening to endless boring lectures on the most conservative of safety guidelines. Certainly safety is important, but to truly understand what safety means you must at least probe in the direction of danger.

At the car we indulged ourselves in the one excess we allowed - two warm Canadian beers each. It had become our reward for every successful ascent. By now our conditioning was so complete that whenever we heard a beer advertisement, we had a strong desire to go climbing.

That night I dreamed I lay in an endless range of mountains. It was that time before sunrise when the stars begin to fade and the eastern sky starts to glow. Above me stood a towering dark figure, gripping a mug in one hand and chanting a strangely familiar mantra: "Sles-se, Sles-se, Sles-se." Then a terrible roar entered my consciousness. I opened an eye. It was not a dream. As usual, Don was up at first light to start the stove for his breakfast, even though we had nothing planned for today. With a groan I rolled over; normally I am not an early riser.

|

|

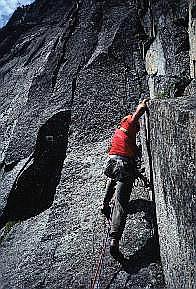

Starting the crux pitch

on the direct start |

Reality hit hard at the Canadian border, where we spent an hour trying to explain what two smelly derelicts from New York and California were doing in a car from New Mexico. The border guard, refusing to believe the computer when it pronounced us clean, instead trusted his own nose. Outside the checkpoint, waves of heat rose from the parking lot, while the inside was packed with impatient tourists heading for the World Exposition in Vancouver. After the guard made several mysterious long distance phone calls, everyone was choking in our stench, and to the relief of all parties we were allowed to continue.

To avoid further difficulties, a quick shower seemed prudent. Don had his own method of obtaining a free shower, and we scanned for the bizarre ingredients: a fast food outlet and large, empty parking lot. Don emerged from the local Wendy's with several gallons of hot water in a water sack and then hung it off the door of the car. Here we proceeded with our business, clad in shorts to avoid offending the local K-Mart shoppers.

"You ought to put all these ideas together," I told Don as I lathered up. "Call it Fifty Classic Climbs on $10 a Day."

Don was not amused, and returned to Wendy's to do some laundry, while I laid out a tarp and basked in the sun. What a contrast to our last visit here only days before. A thin soapy stream was winding down the parking lot, and a nervous manager appeared in the doorway of the K-Mart. When Don returned, I told him we should get back to business.

That evening we bivied at the base of Slesse. Above us the northeast buttress rose as a mysterious starless gap. In the broken rubble where we scratched out spots to sleep was a reminder of a terrible tragedy. In the winter of 1956 an airliner had crashed into the summit, with a resulting loss of all 62 passengers. Grim evidence lay all around us. Small, unrecognizable shards of twisted metal were a humbling reminder of the awesome solidity of a mountain.

|

|

The crux pitch

on the direct start |

A year earlier, under similar circumstances below South Howser Tower, another of the Fifty Classics, Don had argued forcibly against taking my camera along. According to him, photography during a long climb was a waste of time, and with the extra weight we could be forced into a bivouac. After a long argument I had placed my camera with the gear to be left behind, but in the morning I smuggled it aboard. When my deception was revealed by the telltale click of the shutter, Don was furious. He refused to use the camera during my leads and even threatened to jettison it. In the end we completed the climb without a bivouac, but Don exacted revenge by pilfering several of the slides when we viewed them months later.

By the time sunlight hit Slesse's buttress we were already several pitches up. I paid out rope with one hand while taking pictures with the other. This time Don had grudgingly allowed my camera aboard, although he still refused to use it. Every few minutes a terrible crashing from above caused the leader to freeze. Huge blocks of ice, some as large as cars, came tumbling down slabs only a hundred yards away. In the first rays of sun, the glacier beside the buttress was disintegrating. Although we knew that our position on the crest of the buttress was completely safe, we were always shaken by each performance.

|

|

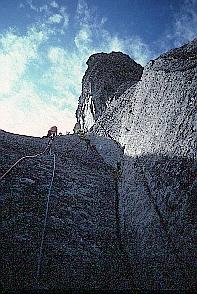

A dihedral in the middle

of the climb. |

Only a week remained in our trip, and on the summit Don began to visualize the possibilities for next year.

"You interested in anything for next summer?" he asked. "How about the Cirque of the Unclimbables?"

It was not hard to guess what had fueled his interest. Lotus Flower Tower, one of the most beautiful of the Fifty Classics, was located there. I had dreamed about such a trip myself, but told him the bad news about the area: the expensive helicopter ride in. As usual, Don had a crafty plan worked out to avoid this. It seemed to amount to helicopter hitchhiking; he indicated that a friend of his had gone in this way. I was skeptical.

We had a long descent ahead of us, and were wasting precious time talking. Hours later we found ourselves once again looking down an unavoidable snowfield, without ice axes and in sneakers. These slopes were usually not much of a problem to descend as long as the snow had softened enough. This one had baked in the sun all afternoon, so I grabbed a pointed rock and started cautiously down.

|

|

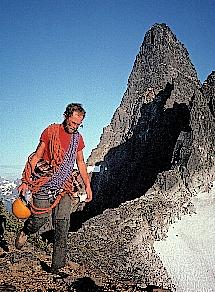

Don right before the hairy snowfield Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

I yelled up to Don, who had been watching all this, to set up a rappel since he had the ropes. Since it seemed ridiculous to rappel a mere thirty-degree snowfield, he began to descend in the same manner. A few minutes later he also finished in the same way, except that he landed badly; his foot was sprained or possibly even broken. Since it was swelling rapidly, we iced it. Our situation was more unfortunate than dangerous: now we would not make it back to our sleeping bags, but we were near timberline and within easy reach of firewood.

After loading Don with aspirin, I walked to the top of a ridge to survey the rest of the descent. The oblique lighting provided a dramatic view of the route we had just climbed--an incredible flying buttress plunging over 3,000 vertical feet from the glowing summit spire down into the dark abyss below. Although Don had complained that the climbing had been easier than he had expected, on sheer elegance alone this route made my personal list of classics.

The fire made the unplanned bivy pretty luxurious. By morning Don's foot had improved; apparently it had just been badly sprained. But we soon dropped too low and faced a typically horrendous Pacific Northwest bushwhack. Fighting under a net of slide alders, we vowed that should we ever escape, we would exact our revenge on its cousins by destroying an all-you-can-eat salad bar.

By the time we got back to the car, Don had become fed up with bushwhacking and suggested a marathon drive to the Wind River Range in Wyoming. I had to admit I was tiring of the vegetation and changeable weather in Washington. We now had nearly exhausted our hit list of the area and if we stayed would be forced back to the REI library or onto more of the Fifty Classics. I was resentful of the way the book had been running our lives lately. Both of us had already done the two Classics in the Winds, so we would be free to do whatever we wanted.

In the Winds I was amazed as we completed climb after climb, all beautiful lines on excellent rock, and of remarkably similar nature to the two Classics just across the way. It brought home a point that I had not realized on my first trip to the Winds: that in any area containing one of the Fifty, numerous other climbs of comparable quality lay nearby. It was only a matter of hunting them out. Although the Fifty Classics provide a good introduction to an area, they were hardly the final word. During my first trip into the Winds, I had been too obsessed by the two Classics to see this.

When I last saw Don that summer, he stood in a secluded corner of a Safeway parking lot, preparing his usual shower. I had to return to California; Don had another month to spend in Colorado.

"Next summer," he said, "give a thought to the Cirque of the Unclimbables."

I could feel the pull of the beautiful Lotus Flower Tower. The incredible photos showed perfect cracks rising up as far as the eye could see. I would have to take another look at The Book. It had already lured Don and me into so many adventures. Still, I could only wonder what other gems lay hidden out of the spotlight for those who turned from its glare.

"Sure, why not," I answered. "There's got to be something worth doing there after we finish with that damn tower."

Postscript: Two years later, Don and I did visit the Cirque of the Unclimbables and climb the Lotus Flower Tower plus several other climbs.

2020: Don Mank passed away at age 66 on October 1st, 2019. We had drifted apart in recent years, and I didn't realize his health had declined rapidly. It was sad to lose such a safe and motivated climbing partner.