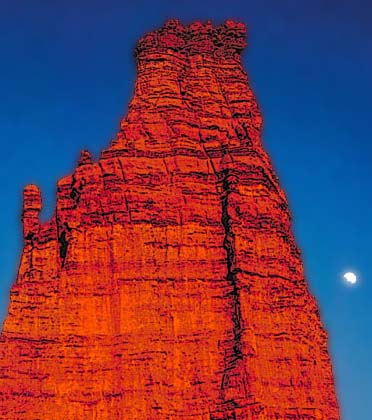

Our ascent route followed the left skyline

(prominent pinnacle is the Finger of Fate).

Copyright © 1994 by George I. Bell.

Written May 1994

[Click on any image for the full size version ~40KB]

|

|

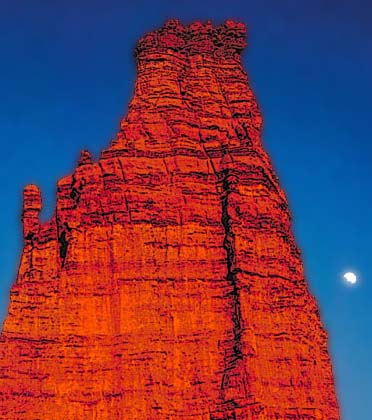

The Titan and moon to the right, at sunset.

Our ascent route followed the left skyline (prominent pinnacle is the Finger of Fate). Copyright © 1994 by George I. Bell. |

My first exposure to rock climbing came via the cover of National Geographic in the late 1970's. It showed Doug Robinson climbing on Half Dome. Inside the issue was an article about the first clean ascent of the Northwest face complete with incredible photos by Galen Rowell. I was blown away but what they were doing and this Prodded me to research this crazy sport further. I went to the library the next day and, not knowing any better, looked in the National Geographic index for more articles on climbing. I found an issue dated November, 1962 with an article entitled "We Climbed Utah's Skyscraper Rock." It was written by Huntley Ingalls and detailed the first ascent of the Titan, led by a climber called Layton Kor. Kor was later to become a hero of mine as I found out more and more about him.

The first ascent, funded by the National Geographic, was made over four days and culminated on May 13, 1962. Layton Kor led every pitch and was supported by Huntley Ingalls, and George Hurley. Hurley also made the second ascent four years later. The route was called the Finger of Fate because it passes a very prominent gendarme on the east ridge.

Bill Forrest, an avid Fisher Towers climber, once wrote: somewhere between standing at the base of these grotesquely shaped, wind and water carved monoliths, and standing on their summits, is a priceless encounter with true grit. If this is true, and it definitely is, then Rob Slater must be Rooster Cogburn because his intent was to be the first person to climb all the Fisher Towers and this includes the truly rotten Mystery Towers. I don't know if he has completed this task yet.

Soaring 900' on it's downhill side (and more like 700' on the uphill), the Titan is the tallest free standing spire in the Colorado Plateau region (with Shiprock being a mountain and not a spire). Perhaps it is the tallest spire in North America. In the whole world probably only such spires as found in Patagonia and the Trangos in the Karakoram exceed it in height. And these are solid granite!

The Fisher Towers abut the La Sal mountains and receive more precipitation than the other spires in the region. When the rain does come the abrasive mud (abrasive enough to almost cut through a rappel carabiner on one descent) cuts runnels and grooves in the tower before hardening into a mud layer. The Titan's lower flanks consist of Cutler Sandstone and the caprock is Moenkopi. No where else in the Colorado Plateau does such rock exist.

George Bell, fellow fifty classics bagger, cynical author of "50 Crowded Climbs" (published in Ascent), rec.climbing reader/poster, was also interested in the Titan and we decided to attempt it. George is a muscular six feet tall with a full beard and professorial glasses. He is always laughing. Not so much a jovial guffaw as it is a nervous laugh that ends most of his sentences. Or maybe he is just a very happy guy. He wanted this tower but up until now couldn't find a partner. I had a similar problem. When I suggested this tower to a couple of desert climbing friends (hi, English Bob), they scoffed at me and said they weren't climbing up that big mudpile just because it was in "50 Classic Climbs of North America." But it was more than that for me. This is simple one incredibly awesome looking tower!

The introduction to "50 Classic Climbs" reads "no one has yet even climbed half of these routes." Obviously that situation has changed and I would be curious what is the most routes done (I know it isn't 50)! George has nearly 30 and Hans Florine did something like 20 in 20 days!) Anyway, upon discovering this book in 1983 I made it my goal to climb 25 of these routes. If successful, the Titan would be number 25.

George borrowed a bunch of pins and we pooled the pins we already had. Then we both bought a couple of baby angles to use as desert bolts if we needed to back up the belays (we didn't use these pitons at all.) We planned on leaving Thursday night after Ilana Stern's (of rec.climbing) party. Ten of gathered to watch Eugene Miya's Antarctica tape (capsule review: mildly interesting, in need of commentary and more humorous shots of Eugene. Best part was snowmobile pulling skiers over a jump.)

And so we set off to climb Kor's route almost exactly 32 years after he did. First we drove to Breckenridge and then after five and a half hours of sleep drove on to Grand Junction for breakfast. We didn't get to the Fisher Towers until after noon. We sorted our gear and loaded up pins, hammers, aiders, slings (long and short), friends (big and small), stoppers, kneepads, buttbags, fifi's, tricams, hooks (yeah, right!), jumars, helmets, rock shoes, clothes, water, food, cameras, and two ropes and started the approach by 1 p.m.

The approach follows a great trail that winds up against a number of the towers. It passes right below Ancient Art and Cottontail Towers. These are some steep walls! On our way in we saw a couple of climbers heading our way. They had just climbed Ancient Art (mostly free at 5.9 with a scary bolt ladder (or 5.11 face)) and were raving about how cool the route was. The corkscrew summit of this formation looks insane to climb up on! They asked where we were headed and when we answered all he said was: "That's a long, loose climb."

After hearing about the relatively moderate nature of the four pitch Ancient Art and the warnings of our intended route, I started to get worried. I remembered how common it was to get my ass kicked on a first trip to a new area. It had happened to me in Zion where I didn't get up anything big. It had also happened to me at Red Rocks. And to friends visiting Yosemite. This would probably be the same, I told George. But that was okay. It was our first trip here. Maybe we should try something smaller than a Grade V to get used to the rock and the climbing? George ignored all this and we kept on walking closer and closer to what I was beginning to think of as certain doom on the Titan.

We didn't have many alternatives. Our route, while long and fairly hard, was still one of the easier routes in the area. Most of these walls are so devoid of any cracks, so continuously steep, so amazingly rotten pieces of shit that I couldn't imagine anyone climbing them. Jim Beyer has put up a number of routes in this area, frequently solo and either not reported or reported only vaguely. Looking at the walls he supposedly climbed, I have my doubts. I would love to come watch one of these ascents, but I feel I would be like those fans at Indy that are just waiting for a crash. The entire hike in we can clearly see Castleton Tower, The Priest, The Nuns, and the Rectory across the way. Already I longed for the relatively solid (Wingate Sandstone) and relatively short climbs on those nearby towers.

We first walk by King Fisher (the second tallest spire) and Ancient Art. Next we pass the twin towers of Echo and Cottontail. On the west ridge of Cottontail is a horrorifying route called Brer Rabbit. It was put up as a solo by Ed Webster in 1978. Finally we reach the granddaddy of them all, the Titan. To approach our route we need to go completely around it and back north on the other side. Our approach brings us right by the foot of the Sundevil Chimney route on the south face of the Titan. This is truly the jewel of the area, but at 5.9 A4 and a grade VI, out of our league. The route is a direct shot from the foot of the tower to the very summit. It starts with an almost invisible crack on a slightly overhanging wall (A4) to a forbiddening, mud groove that shoots straight up to cleave the summit block. Harvey T. Carter, the prolific desert climber did the first ascent of this route over eight days in 1971. I think it was recently climbed as a "warmup" for Charlie Fowler's clean ascent of the Shield. Is this true?

I forgot one of my aiders, my fifi, my butt-bag. Was I psychologically trying to sabotage our attempt? George would have none of it. He brought four aiders as he likes to lead with four so now we had three to lead with (George constantly bitched about this) and two to jug with. He also brought two fifi hooks despite having never used them before. Finally, he lent me his butt bag at the one of the hanging belays. This man was not to be deterred. Climbing the Titan in the rain is the only thing crazier than climbing it without a helmet. These towers are supposed to flow with mud during a rainstorm, but they shower with sand and rocks when below a leader such as George "The Master Blaster" Bell. George's motto is: why place a dicey friend in a mud crack when you can pound in a good angle piton?

George wanted to flip for the first lead, but I wouldn't have any of that. I wanted the first lead because it was supposedly easier than the next lead. From the ground it looked like it might go clean and since I had never pounded a pin in my life, I thought this was the best strategy. I just starting racking up as if that was the team decision.

We carried two topos for the Finger of Fate route. One from an old Rock & Ice issue and the other from Eric Bjornstadt's guidebook Desert Rock. The disturbing aspect was that they weren't very similar. Thankfully, the easier R&I topo would prove more accurate.

pitch 1: start at 2:30 p.m. free climbing, clean, getting onto pedestal, my first pin, free climbing above a tied off pin and then pulling on a half cam technical friend. Yikes! Hanging belay 140 feet up. Long time to lead this. This was scary! I thought to myself what the hell was I doing up here? I wondered why I really climbed, or at least why I climbed long, scary, committing crap like this. Maybe I should give up doing long, hard routes. Stick to short 5.7s. I had experienced such things before but not for awhile. My last big climb was two years ago. Always these feelings of fear would fade very quickly and before I knew it I was doing another committing climb, but it felt deeper this time. I was coming to an impass in my attitude and I could either turn around and run or persevere and continue on. I half joked with George as we passed the rack between us that if I dropped the rack we would have to go down. Then I promptly did drop a carabiner containing two pins.

George could sense my trepidation and tried to remain enthusiastic even when he was having doubts himself. When I finished my long, draining lead I had two immediate, all consuming thoughts. First, that I had done all the leading I would be required to do...today. I just needed to hang here and belay now and then I would get to go down. Second, that no matter how scary that first pitch had been, I was glad I did that one and would not have to lead the horror above me. I secretly hoped that George would agree when he got a close look at it and we would both agree to retreat. Unfortunately when George arrived at the stance he didn't hesitate in grabbing the rack, laughing about the horrendous looking prospects, and immediately start bashing in pins.

The shower of sand and small pebbles was only interrupted by the occassional large dirt clod that whistled by, smashed near me, or hit me. I cowered with head bent at the shelterless hanging belay and tried to line up my head with the rest of my body so that my helmet would take the brunt of the debris. A slam on the back of my neck coached me into the proper form. I was climbing with the Master Blaster so I guess that made me Mad Max. Well, mad anyway.

pitch 2: 70 feet of mostly nailing up a rotten seam. Interesting placements. No crack existed here before. None. Not even a seam, but thin vein of different, softer mineral deposits. Instead of drilling a bolt into this blank surface, I surmise Kor drove a knifeblade piton straight into blank rock (albeit very soft, muddy rock.). Subsequent ascents have expanded the size of these holes into nearly round inch and a half angle placements. Most placements need to be tied off.

Retreat due to lateness of the day. It was 6:20. I setup the lower rappel while George rappeled and cleaned the pitch he had just led. I was quietly thankful for not having to clean the pitch. It was scary up here and jugging is a scary prospect anyway. So, after two pitches I had placed two pins and still hadn't cleaned one. We had hoped to get the next pitch fixed also, but now I could lead this next pitch and avoid the crux, or so we thought at this time, roof pitch.

Two pitches in four hours. One was only half a rope length. Things did not look good. The climbing above looked hard and we knew the crux was still above us. Hiking back to the car that night I had serious doubts. I racked my brain for a good excuse to get George to give up the climb. I briefly pondered tripping on the way out and injuring my ankle (this is easy for me to do), but resisted the temptation because the Bolder Boulder was the following weekend. We started hiking out by 7:30 after stashing our gear at the base and made the trailhead at dusk.

Dinner, sleeping by the car, alarm set for 5 a.m. constant arrival of cars all night long. Long conversations just 30' from our comatose forms at 3 a.m. Who are these jerks? We'll be certain to make a similar amount of noise when we get up to pay them back.

Two climbers left the camping area with large packs at 5:30 in the morning. The target I had planned for us to leave. It didn't take a lot of imagination to guess what route they were headed for...We left at six with light packs, carrying only water, camera, food, and clothes. We caught them in the final gully and their first words were "pretty sneaky coming up here on a Friday!" They had noticed our ropes and halted their approach. They had been halfway up the route before and were coming back for another attempt and hoping to do a one day ascent. Our ropes ruled out their one day attempt since leading below us would be at best unpleasant. The two climbers, bespectacled, thin, young, and nerdy looking (this is in no way meant as a slam, but merely as a description) appeared to be brothers. They mentioned casually, as if we had just bumped them from a short easy route with no preparation or approach, that they would just climb something else. I was tempted to say "Well, the Sundevil Chimney route appears to be free," but instead said nothing.

They mentioned that the next pitch was going to be the crux. I immediately switched my strategy to talking George into that lead even though it was my turn. Let's see...It was really the continuation of the pitch he had started the day before. It was the crux pitch and involved nailing and he had much more experience at it. This proved effective and I was sentenced to another rock shower below the Master Blaster and the scary overhang pitch above, but I avoided the crux.

Partners who have climbed with me will be amazed that I am trying to duck leads. I am usually a lead hog. If anyone wants to know a cure for lead hogging, I have it: The Titan! The rock on this beast makes Castleton, Moses, Indian Creeks, etc. look like Yosemite granite.

On the Rock and Ice topo, the third pitch has the ominous byline: "A3 pin in mud". In reality, the pitch contains many holes about an inch square of varying depths. Not much fits in them except for angle pitons. Vary rarely do you get a chance to slam one of these suckers in these days - now I was placing one after another (thanks to Pete Williams for lending me his entire supply). Most only went in half way and had to be tied off. Some of the holes seemed to slope downward slightly - these were the real scary placements! There was only a piece or two of "fixed" gear so it was very time consuming. Despite Bill's confidence in me, I have never led a bona-fide A3 pitch. I don't know if this pitch is A3, but it was certainly the hardest aid I have ever done.

Bill and I were by now a well oiled team - me cursing constantly to him about having to climb with only 3 aiders. Bill, fuming away each time I would release a volley of sand and dirt on him by my none too graceful movements. There is very little of what would normally be termed *loose* rock on this route. Rather, the walls are a series of bizarre rounded bulges. The top millimeter of rock flakes off easily to the touch and the occasional rounded ledge is invariably piled high with rock dandruff. Often the scariest moves of all were the free ones. I was amazed that some of my tied off pins held body weight, and the thought of an actual lead fall on one of them was terrifying.

At last I reached the belay and the first ledge of the climb. For the past 12 hours I had been pretty well convinced we weren't going to make it. After all, we had taken something like 6 hours to do the first 3 pitches, and these last two were only 70' each! In planning this climb I figured Bill and I had just the right skills and gear to do this climb, but we were clearly not psychologically ready for the bad rock. This beast was a nasty one. Only time would tell if we would make it before sunset. I was determined to give it our best shot.

Bill quickly racked up and started pitch 4. Here you traverse right on a sloping mud shelf, clip a bolt and move right another 5' to the base of an overhanging chimney. The exposure below you begins to open up. Bill slammed in our only 2" angle and I leaned out to see him dangling from the roof, Cottontail Tower in the background. Several more aid moves and he was able to move into the chimney and make some free moves to a belay astride the ridge crest. Following the pitch, I realized that it had taken much less time than the previous three. I didn't want to mention this to Bill to raise false hopes, but it seemed the difficulties were easing.

The climb now follows the narrow ridge crest to the summit. The exposure begins to open up on both sides. The next pitch is an obvious crack up the crest. It is flared and ugly, although not particularly steep. On good rock it would be a nice free pitch. Supposedly this pitch goes free at 5.9+. Ha! Not for me. I was soon back in my aiders. It is also very difficult to aid this crack because it is so flared. In sight of the belay I found myself squeezed desperately into the flared slot. There was barely room enough for my chest together with our gargantuan rack, and the only thing holding my upper body in the crack was an arm bar on this crumbly shit. The crack was very wide here so I had a #4 Camalot at my feet. Even using the aider was hard because it tended to pull my feet into the crack and lever out on my upper body. After some ungainly thrashing and cursing I finally got a hand around the belay slings.

Above me on the ridge sat "the duck", a convoluted boulder the size of a large van ludicrously perched on the narrow rounded crest, supported by what looks like a 2" layer of petrified Doritos. Bill began leading what was to be the only completely free pitch of the entire climb. Stopping under the duck, Bill pounded a pin into it's tail feathers. It rang like a 50 ton bell. "Man, I hope those Doritos don't crumble!", was my only thought. "This pin seems pretty good!", exclaimed Bill. Great. Now our fate is tied to that of this teetering, flightless desert fowl. Bill continued the easy but sparsely protected traverse and continued up a short, funky 5.8 chimney. He was at the bivy spot!

At this point I thought we might just make it. There were only 2 pitches left. We dared glance at our watch - it was only 2:30 PM! We decided to stop and refuel on the biggest ledge of the entire climb.

By 3 I was ready to lead the next pitch. I was feeling good because it looked like a cruise compared to the final terrifying lead. I moved right of the arete and pondered the route. Bjornstadt's topo here says something about "5.6 Rotten, #4 Friends". In front of me I saw another incipient crack with a bolt and fixed pin. To my right was a muddy 4-6" crack behind a very loose looking block. I decided to ignore Bjornstadt and follow the fixed gear (a wise decision, as it turned out). More A2 nailing. I pulled back onto the ridge crest to see a 6 bolt ladder rising above me. This is more fixed gear than is found on all the previous pitches put together! The ridge is not too steep here and except for one overhang the bolt ladder goes free at 5.6. Fortunately the rock here is somewhat more solid than the earlier pitches. Positive handholds, however, are always nonexistent due to the rounded nature of the rock.

I pulled up onto one of the most exposed, wild belays imaginable - an 18" square platform on the crest of the ridge itself. On either side the ridge dropped off in a dizzying series of mud flutings and curtains for over 600'. The ridge above me reared up vertically, studded with bulges and occasional bolts. It looked tricky and horrendously exposed. Suddenly I realized that this was the spot where John Peterson had caught his partner Dave Youkie after a 40' factor 2 fall which had ripped out all the intermediate protection bolts. I had read about this in John's trip report: Adventures on The Titan.

|

|

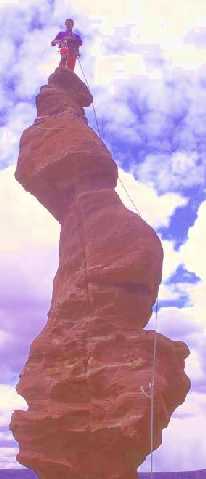

Bill Wright leads the final pitch on the Titan.

Copyright © 1994 by George I. Bell. |

As Bill jugged the fixed line, struggling to remove the pins I had placed I hoped he was up to leading this final pitch - I didn't think I had it in me. I also hoped Bill didn't recognize this spot from John Peterson's description, and I certainly wasn't about to mention the frightful fall to him. There were *only* 5 bolts at this belay, and though some had eroded out a quarter inch or so none wiggled in their holes. Unfortunately, none of them were what I would call bombproof, either. I contemplated placing another bolt, since I had already dragged up our pack containing the borrowed bolt kit. Finally I decided pounding this rock near the other anchors while Bill was jumaring on them might be worse than leaving the anchor alone.

Bill led the final pitch. The bolts that had pulled during Dave's 40' fall had been replaced by shiny new ones. The initial bolts were spaced about 6-8' apart in places, forcing Bill to high step in an aider, then make a 5.8 free move or two until he could clip the next bolt. Eventually the ridge became vertical and the aid became continuous with very long reaches between bolts and fixed 1/2" angles pounded into holes. Finally a long, wide crack with some free climbing breaches the main summit overhang. The haul line now dangled free in space, proof that this pitch was plumb vertical or even slightly overhanging. After the scary jug up, Bill and I were on top of the biggest mud pile of them all! Well, not quite. One more easy class 4 pitch ended at the summit register: a round tin box nailed right to the summit block.

No boy scout troops to be found tossing rocks off this summit, that's for sure! I was eager to see how often this sucker was in fact ascended. However the tin box was empty except for 2 quarters and a tiny hunk of webbing with some names scrawled on it. Bummer. From here we can really see how the Titan towers over all the other Fischer Towers. It feels almost as if we are in an airplane flying over them. The sky is entirely cloudless, a good thing when you are sitting atop the tallest lightning rod in the country! We lower our guard on the spacious summit by unroping, but we are unable to relax completely with the thought of the terrifying descent.

After almost an hour on top, we begin the rappels. Methodically, we check and re-check all the links in the system. Purposefully we have not brought our newest ropes on this climb. Both our lead and haul line have sheaths gritty with sand. Both of us experience an unusual amount of drag in our rap systems due to this. My figure 8 squeals annoyingly and jerks as the dirty ropes pass through it. These ropes will definitely be in for a washing!

|

|

Bill Wright on top on Ancient Art.

Copyright © 1995 by George I. Bell. |

Fortunately the descent is uneventful. Two raps to the base of the 5.8 chimney and platform after the duck, then 3 more straight down the N face (to the right of the route) reach the ground. Bill volunteered to go first on all the raps, which I greatly appreciated (this also gave me the opportunity to knock more shit on him!). Frankly, I hate exposed rappels. People are often surprised to hear that I have a moderate fear of heights. Only after 10 years of climbing have I learned to control it in situations like this.

At the base we finally relax completely and suck on a big 2 liter water jug. We did it! And it took everything we had. We both agreed that we could never have led more than half those scary pitches. The nature of the rock really begins to wear you down on lead.

By 7 PM we repack our gut-busting sacks and shoulder them for the walk out. The low angled sun forms dramatic views of the Titan, and I long for my wide angle lens. At the base of Cottontail Tower, the entire west face of the Titan is burned a brilliant ocher by the last rays of the sun. As the moon rises behind the Titan, we stop to savor this special moment.

Many climbers I have met don't understand why one would want to climb the Titan. I guess I am a mountaineer at heart, and mountaineers always want to get to the top of impossible looking peaks. In addition to the lure of the summit, the upper ridge itself is a masterpiece of nature's artwork and an amazing place to be. I'll certainly never forget sitting under the duck, marveling at it's absurd form and defiance of gravity. As we walked out, Bill and I agreed that this place was too scary to return for another climb. But I will definitely be back some day simply to gawk at these ridiculous "cartoon spires". And there is always Ancient Art - that climb doesn't actually look so bad ... Hmm, I wonder if Bill is up for that one?

Postscript: We did go back and climb Ancient Art in 1995, and the Kingfisher in 1996.